BubsBuilds Projects

- Details

- Parent Category: BubsBuilds Projects

- Category: Assorted (hopefully) "Useful Stuff" Projects

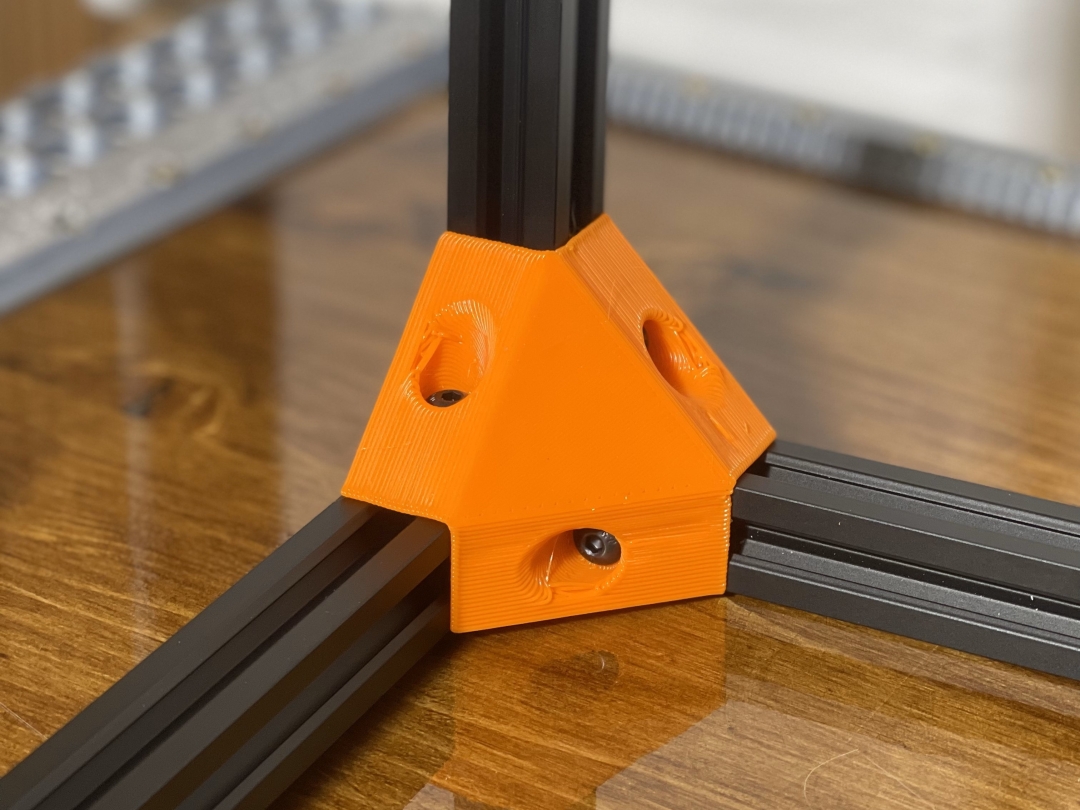

90 Degree Corners

1.25" SQ Wood Frame

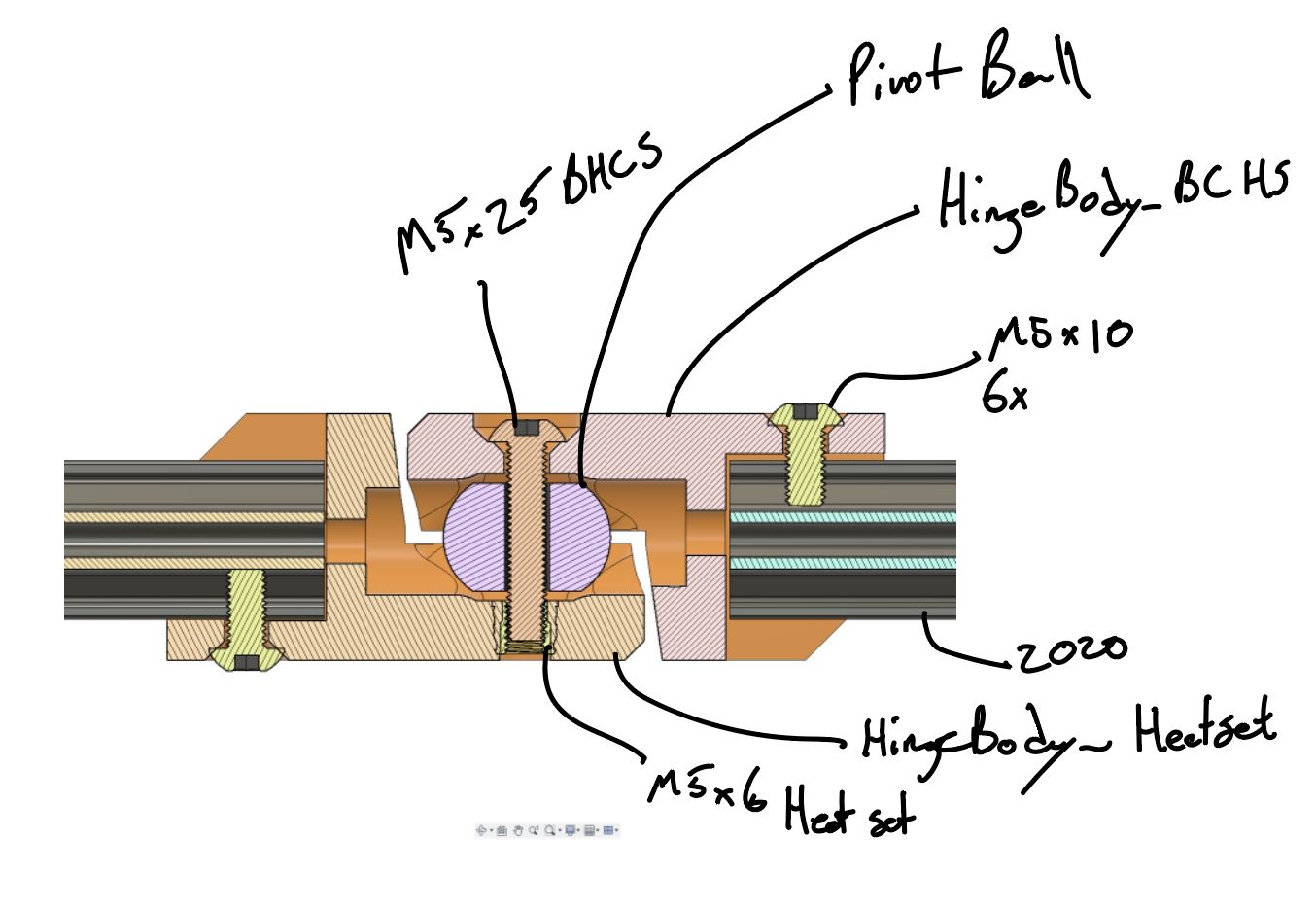

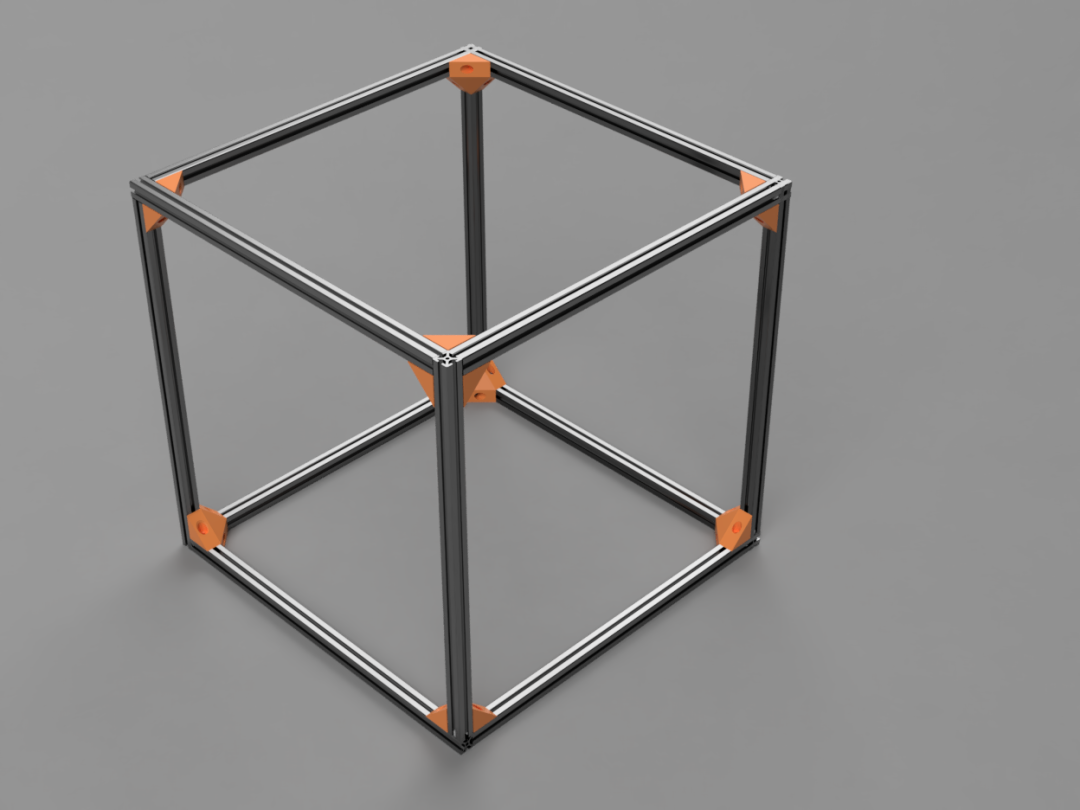

2020 Aluminum Extrusion

I recently had a project that resulted in a small pile of different 2020 part designs, so I started a separate page dedicated to them here: 2020 Aluminum Extrusion stuff

|

|

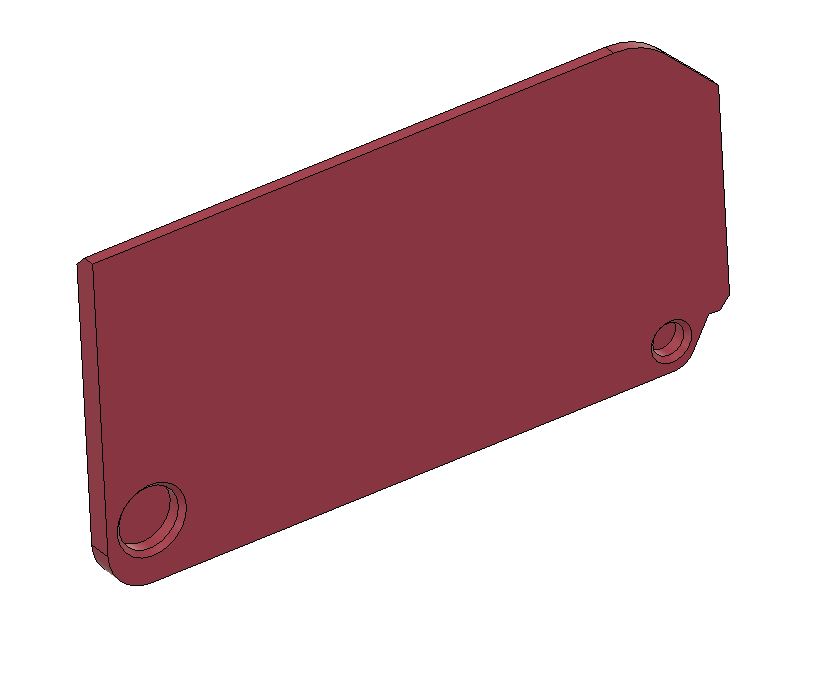

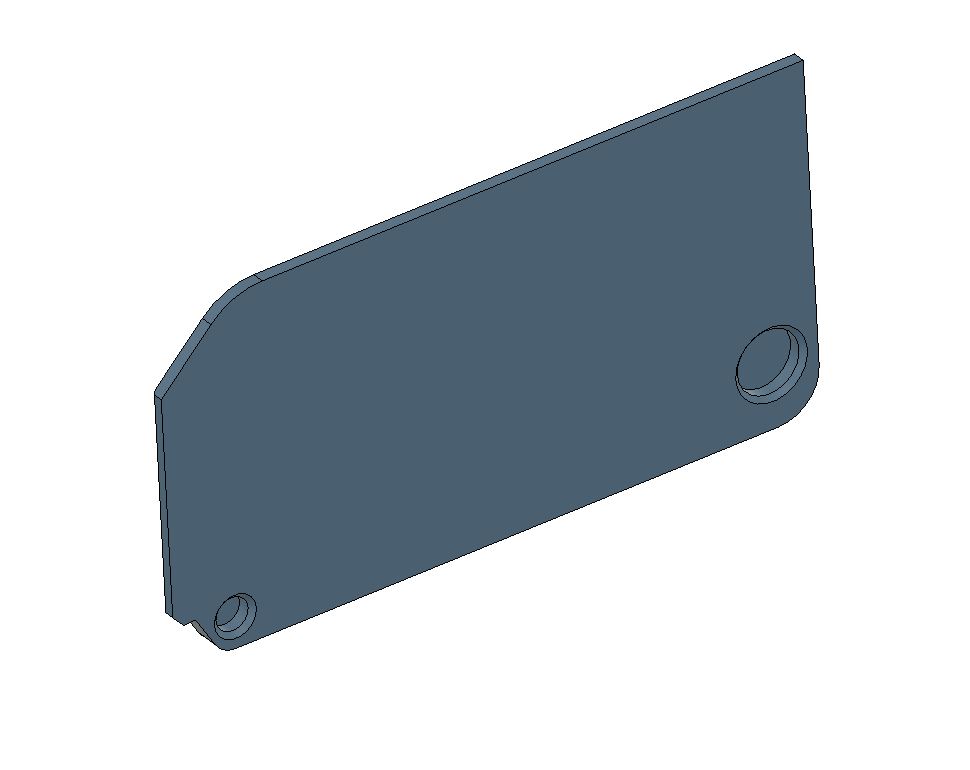

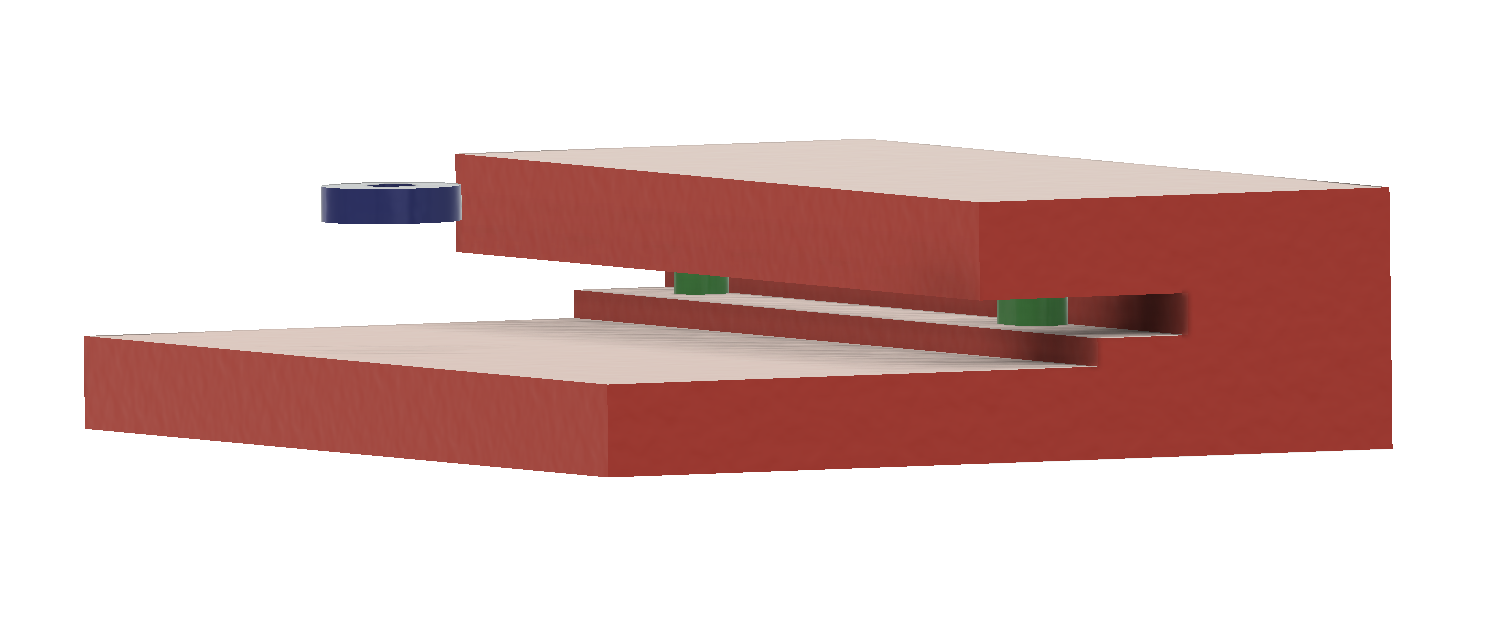

Designed to fasten 2020 Aluminum Extrusions to make cubes with flush edges. Not intended to be particularly high load capacity, but I've built quite a few frames from this general design, and they are working just fine for my needs! Holes are designed for M5x16 BHCS fasteners, but slightly shorter (maybe down to 12mm...maybe...?) should work.

Mine have printed fine without supports, brims, etc.

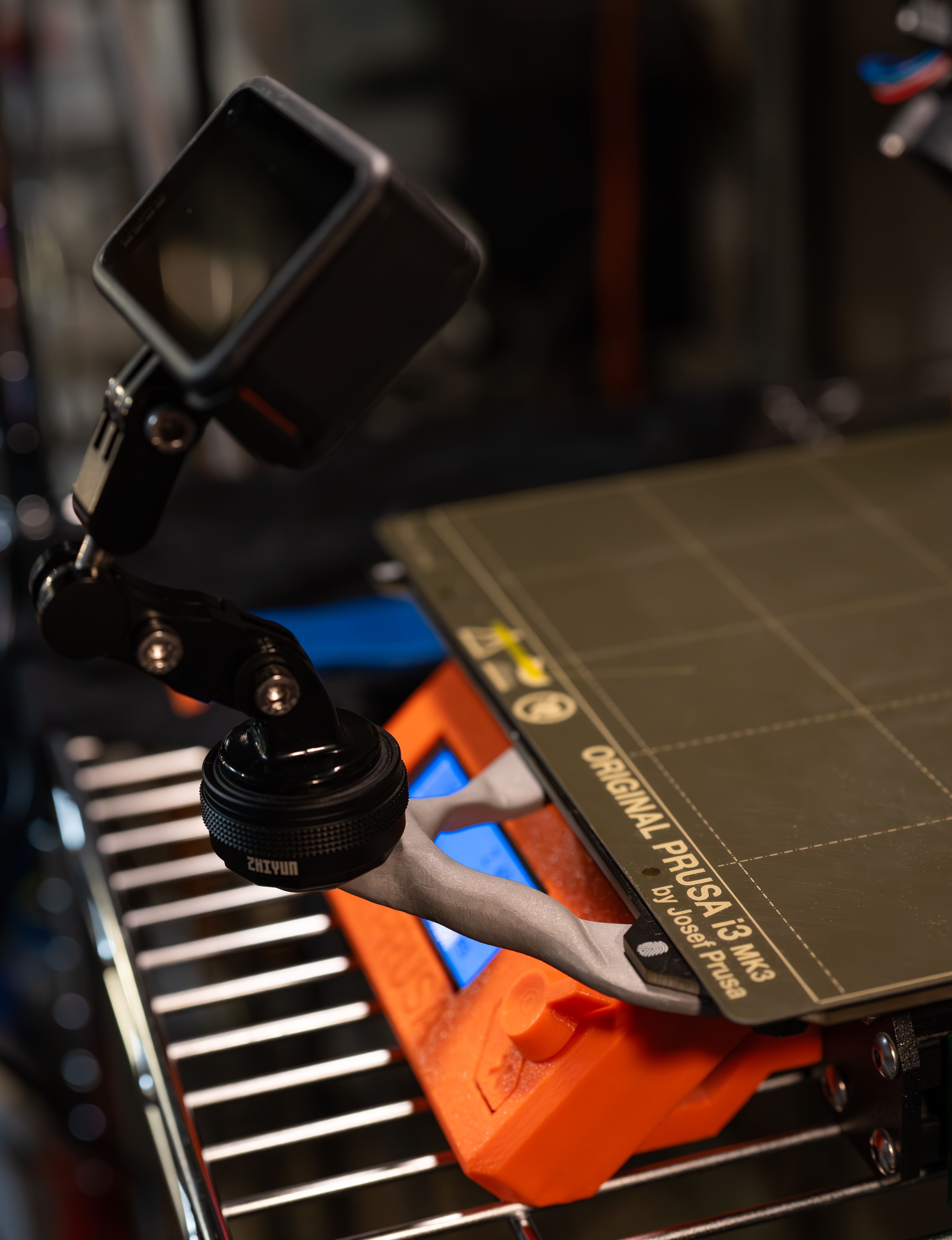

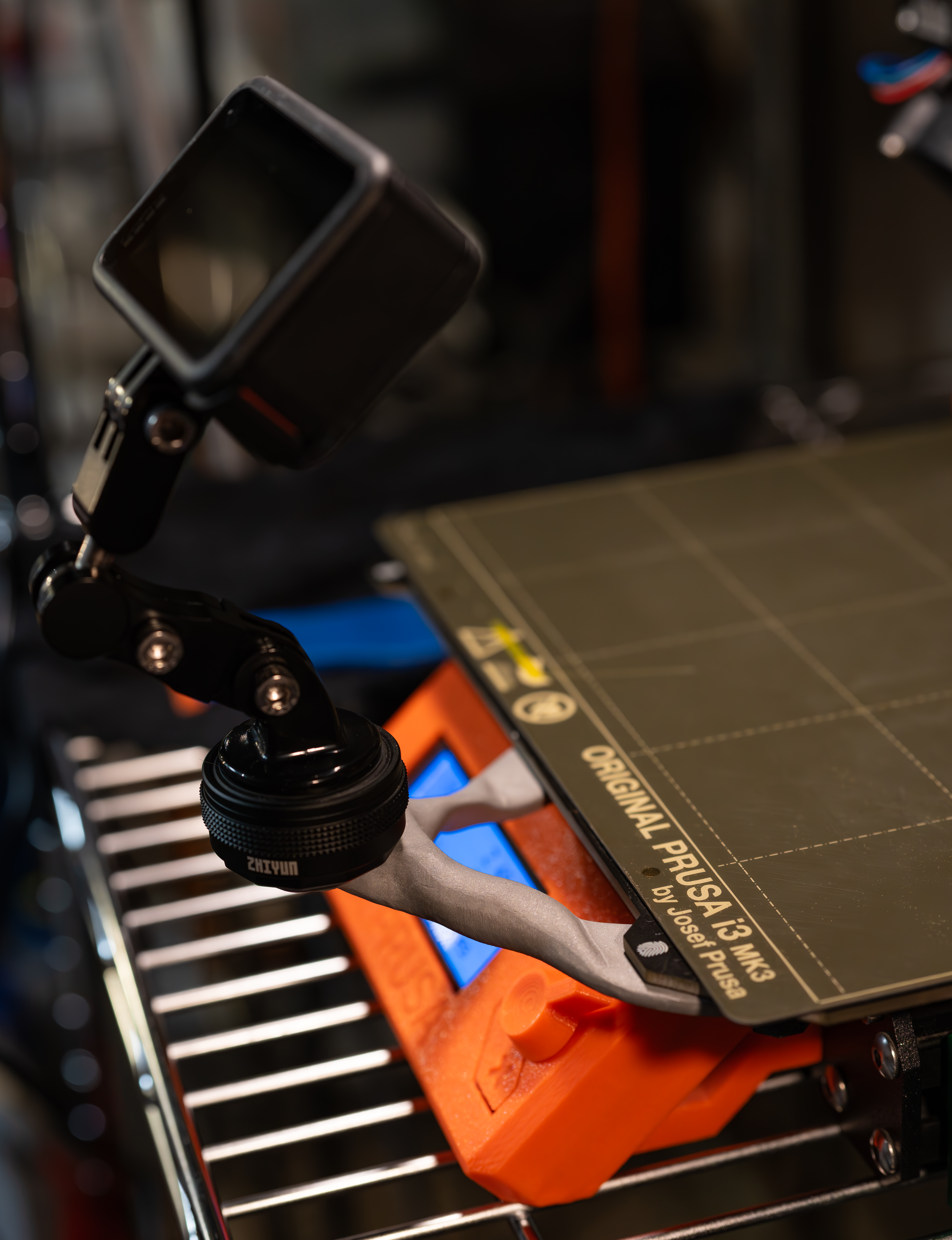

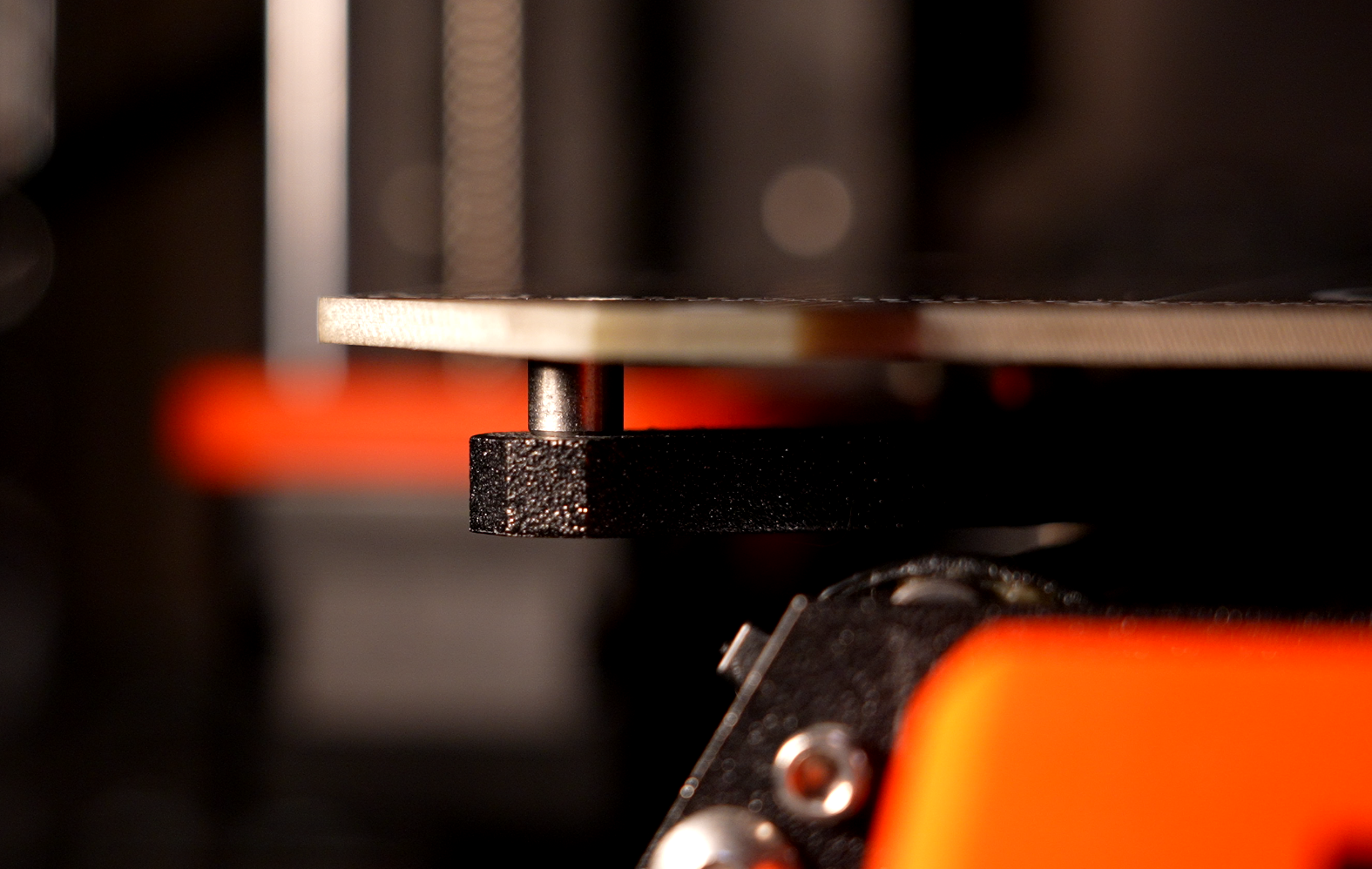

I printed these in Orange Overture PETG with 0.48 layers on a 0.6mm Revo nozzle.

- Details

- Parent Category: BubsBuilds Projects

- Category: Games

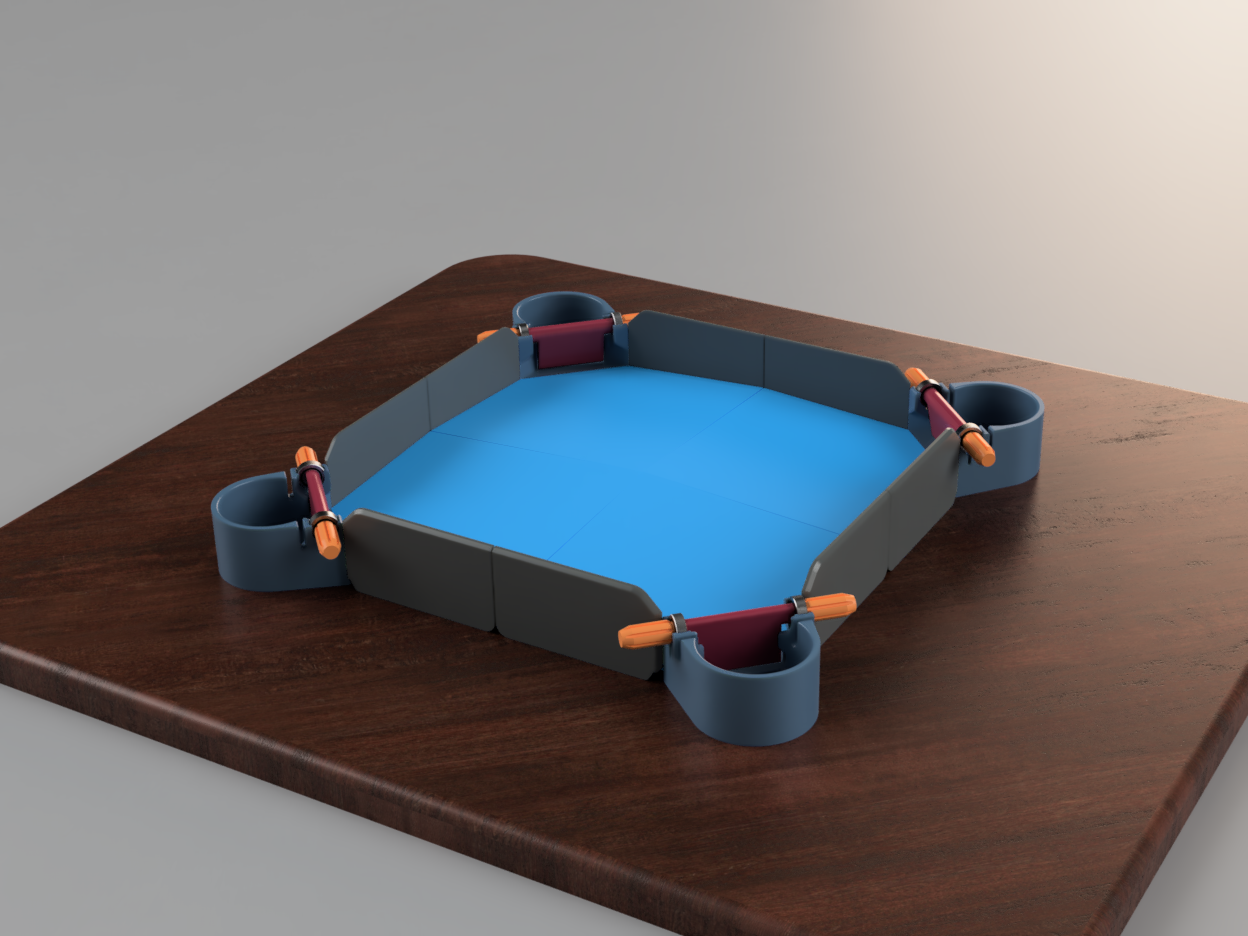

This game was a guaranteed part of every major family get-together with one set of my grandparents (and the exponential growth that followed from their 5 kids). Ok, well not "this" game, but the game that this was inspired by. The idea of the game is you drop balls into the center, and each player is trying to keep their pocket empty and their opponents' full.

I am just printing the last few parts for my first build, and it will be getting its first game night battle testing within the week!

The Build

All files for the printed parts can be found at:

BOM:

- Printed Parts:

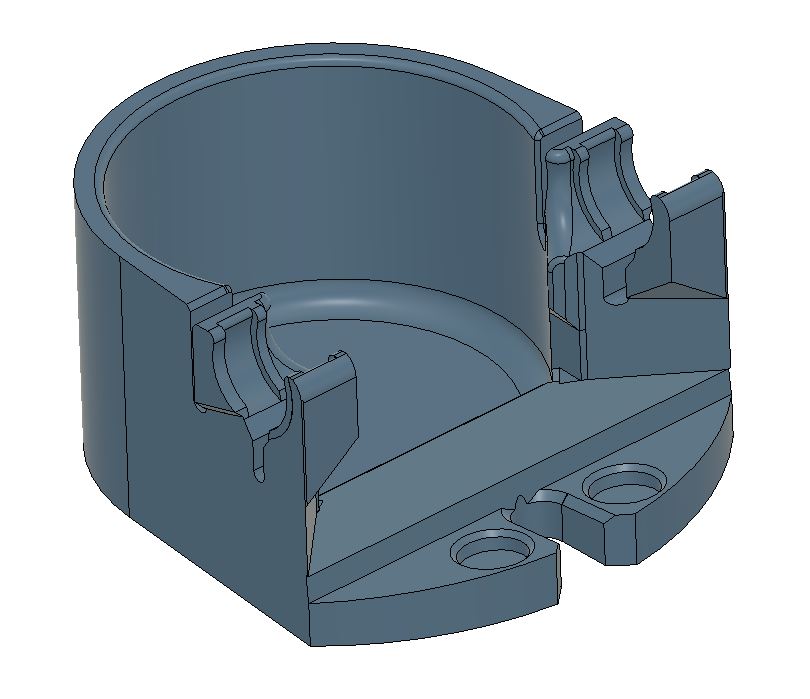

- (Qty 4) Pocket_gen1.stl

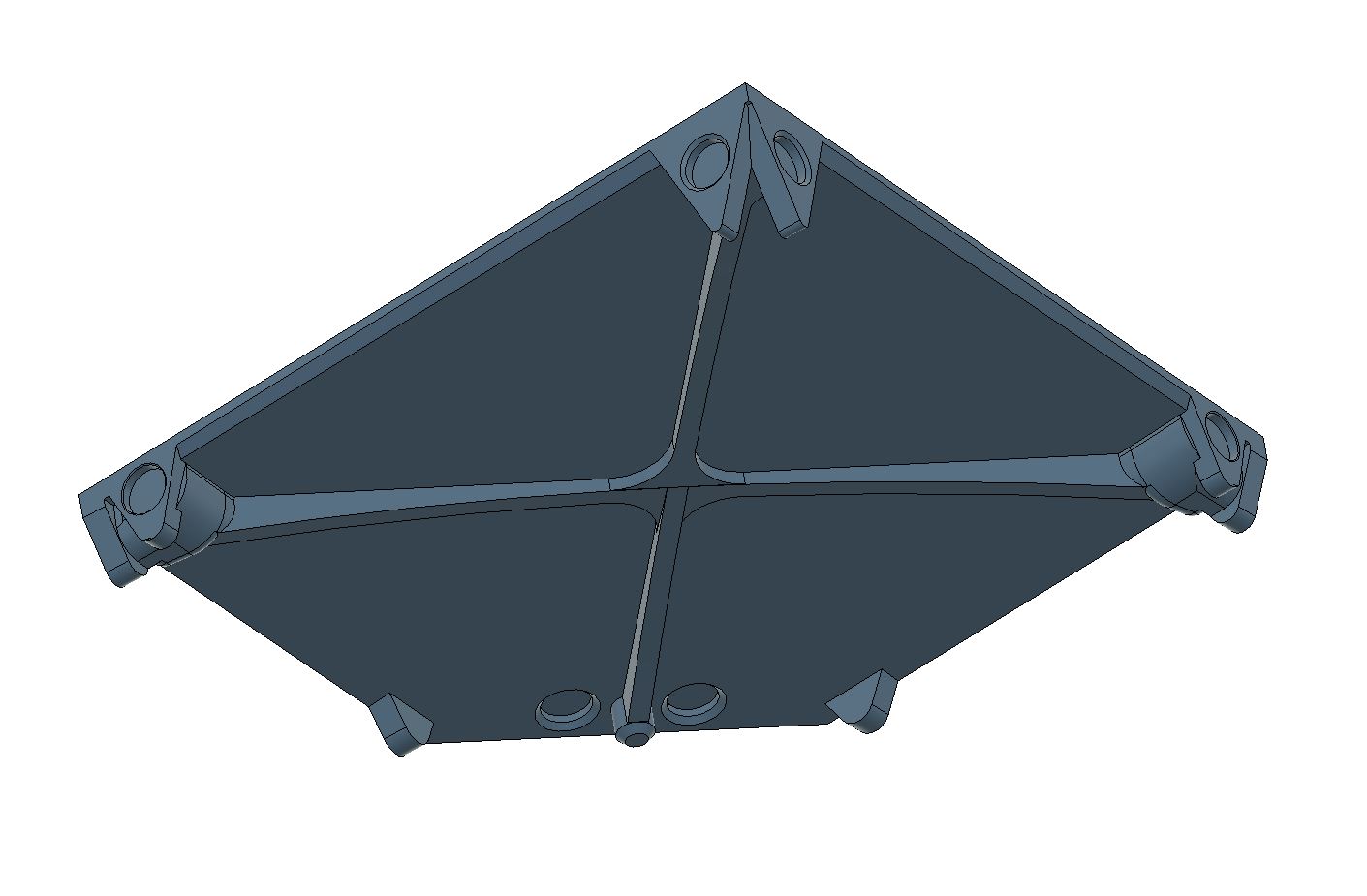

- (Qty 4) Quad_gen1.stl

-

- (Qty 4) Wall_1.stl

- (Qty 4) Wall_2.stl

- (Qty 8) Handle.stl

- (Qty 4) Paddle.stl

- COTS

- (Qty 8) Bearings - I designed it for (and used) 608-2RS roller bearings, aka roller skate bearings. BUT my plan is to switch these over to simple 8mm ID bushings for future builds. The roller bearings are substantial overkill :)

- (Qty 4) 8mm OD x 150mm length shafts - I used ones like these (I got long sections and cut to length, but otherwise this)

- (Qty 48) 10x3 disk magnets

- (Qty 32) 6x2 disk magnets

- "Super" Glue, cyanoacrylate (CA) if ya fancy - I used this medium CA...oh I'm fancy...I like this viscosity for securing the magnets because it has a good balance of penetration into the glue joint but without being so runny that I'm stuck to everything on my desk 10 min. later.

- BALLS - I almost forgot! You're going to need something to kick around. I'm going to start out with these polymer bearing balls.

Assembly

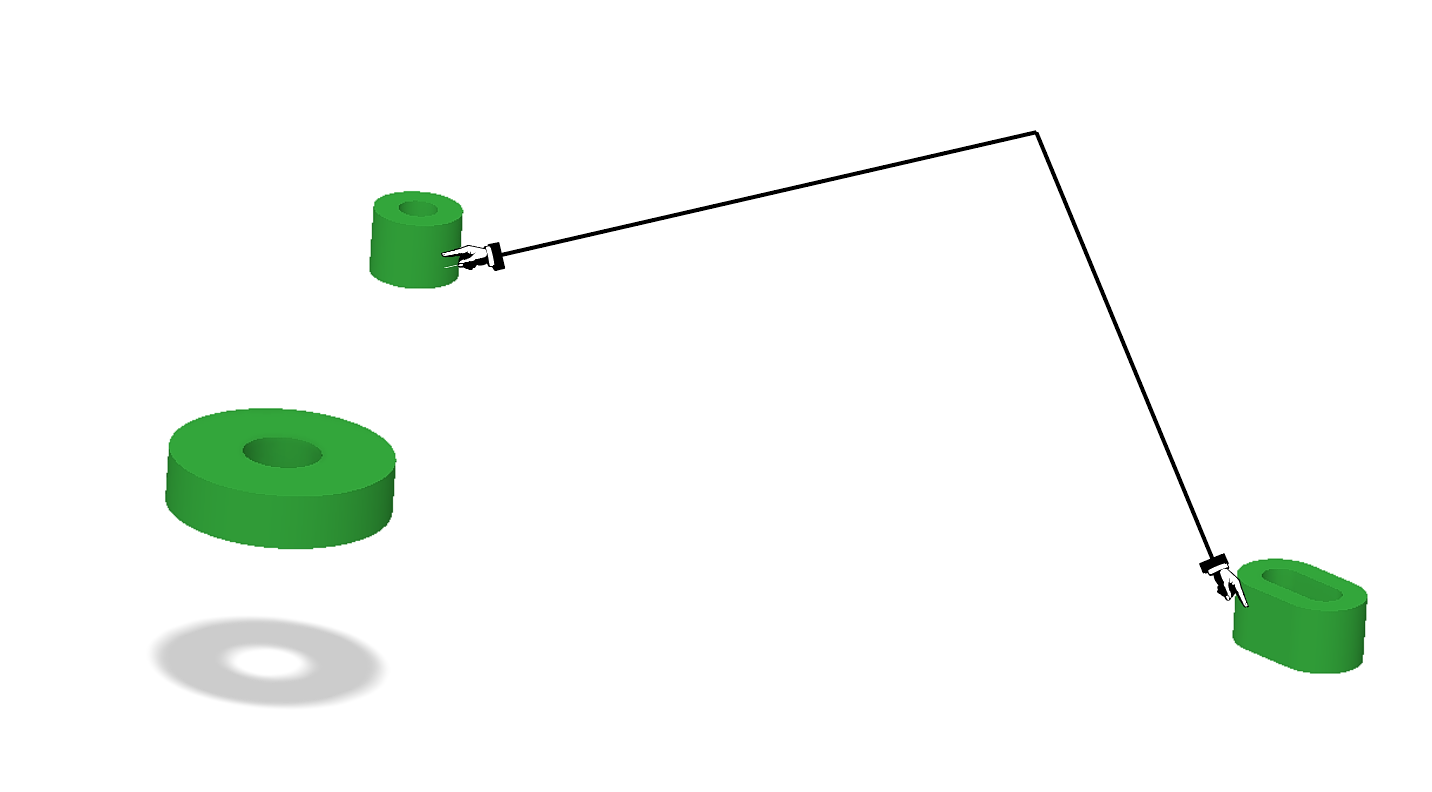

MOST IMPORTANT INSTRUCTION - Be extremely organized and careful with the orientation of your magnets! You don't want to have your board flying apart! Come up with a plan for what pattern of N/S you're going to use for your parts, and just be sure that all interfaces will be attracting!!! I know it sounds trivial...but I've scrapped many-a-part over the years due to unintended maglev kinematic mounts.

|

|

The assembly is pretty straightforward, so long as you adhere to the advice above.

- Glue in all your magnets. I'd recommend doing one magnet pocket at a time and let it cure fully before moving on to the next. Yes, this one can take a while, but if you do all of the parts in parallel, it's not THAT bad. I just set up an improvised 'rack' on a tabletop (made from all nonferrous materials, of course...I love magnets, but they'ze sneaky!) that allowed me to have the Quad parts upright spaced far enough to avoid magnet interference between them.

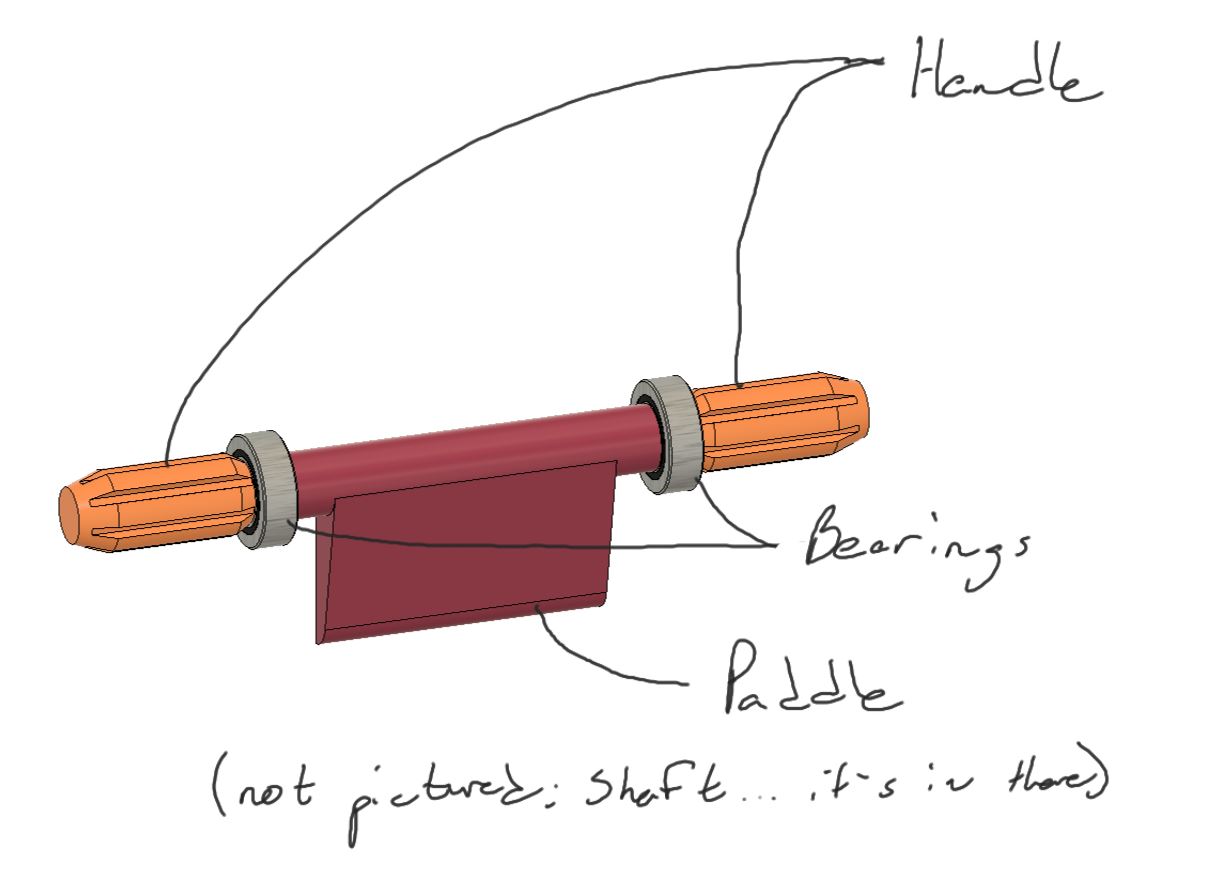

- Assemble the Paddle sub assemblies

- Press on the first handle (if yours has a loose fit, I'd tack it in with some CA

- Slide on the first bearing

- Press on the Paddle. The paddle is split, so it SHOULD expand and slide on (I recommend PETG, or other material with some compliance to it. PLA will almost definitely break for this fella). If it doesn't, one trick you can try, prior to cursing my name...hopefully, is to freeze your shaft (this will work better if you used a polymer shaft, but aluminum might give you enough) in your freezer and heat up your paddle a bit. If your interference problem is light enough, this should do the job. Don't heat the plastic to more than 100C (or look up the glass transition temp for the plastic you choose and just give yourself some margin under that)

- Slide on the second bearing

- Press on the second handle

- Pop the Paddle subs into the bearing mounts of the Pockets. Not gonna lie, I was pretty pleased with myself on these bearing mounts...even though I quickly decided the bearings themselves were overkill :/ I printed mine in PETG, and the bearings click in with a nice, satisfying pop and feel rigid (thus far) in use.

- Let the magnets do the rest of the assembly work, and let it self-assemble!* (*may not actually self-assemble, but once you get the parts close, they do pop together in a way that I thoroughly enjoy.)

- Details

- Parent Category: BubsBuilds Projects

- Category: Generative Design Projects

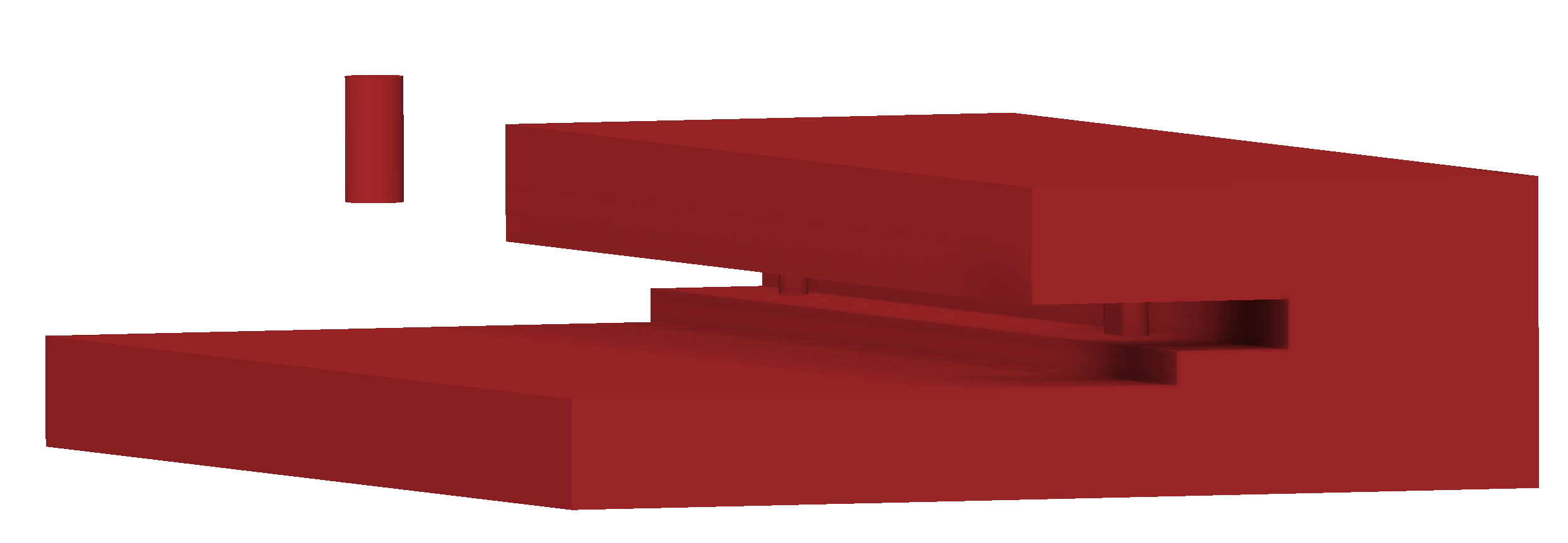

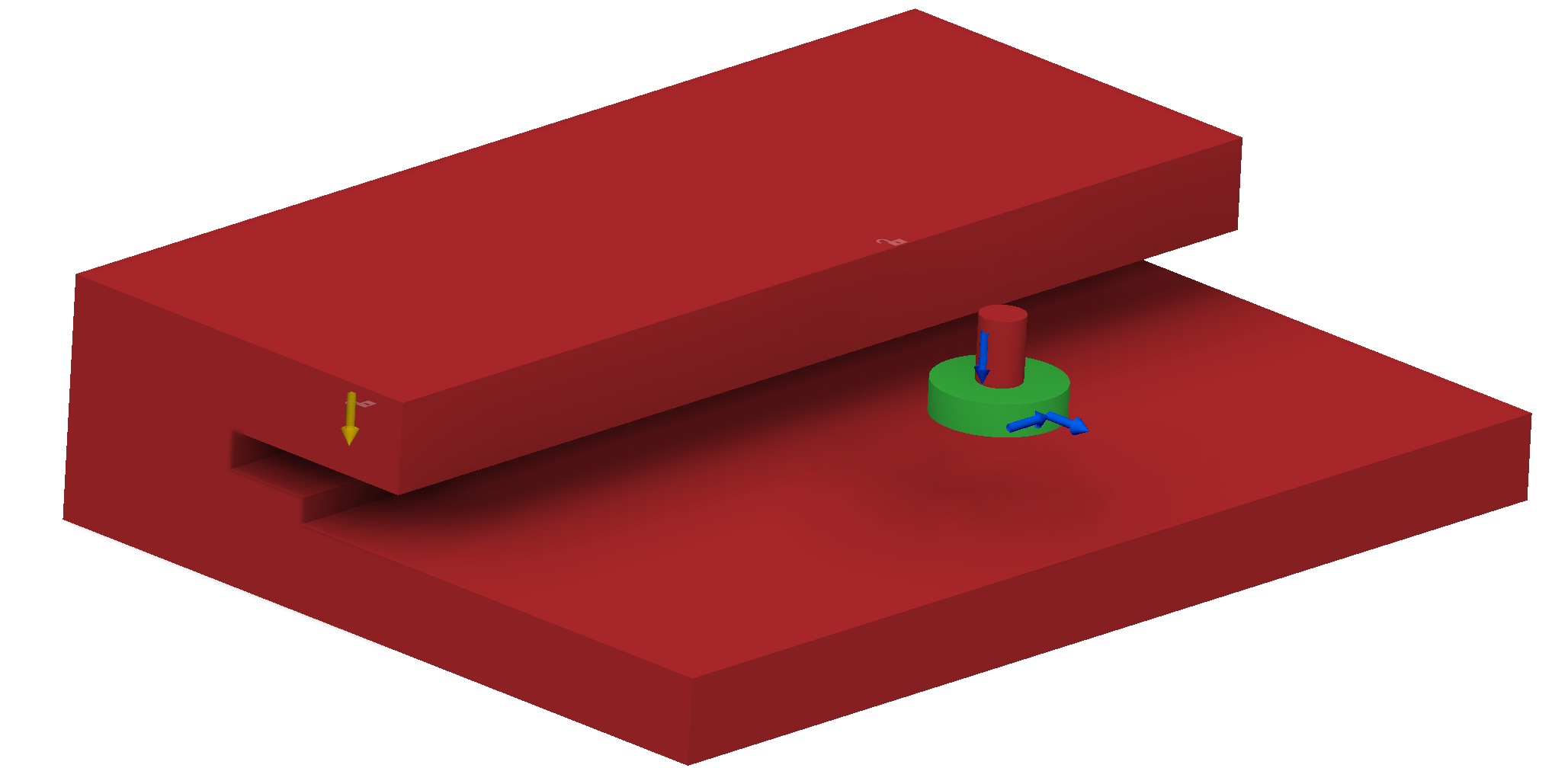

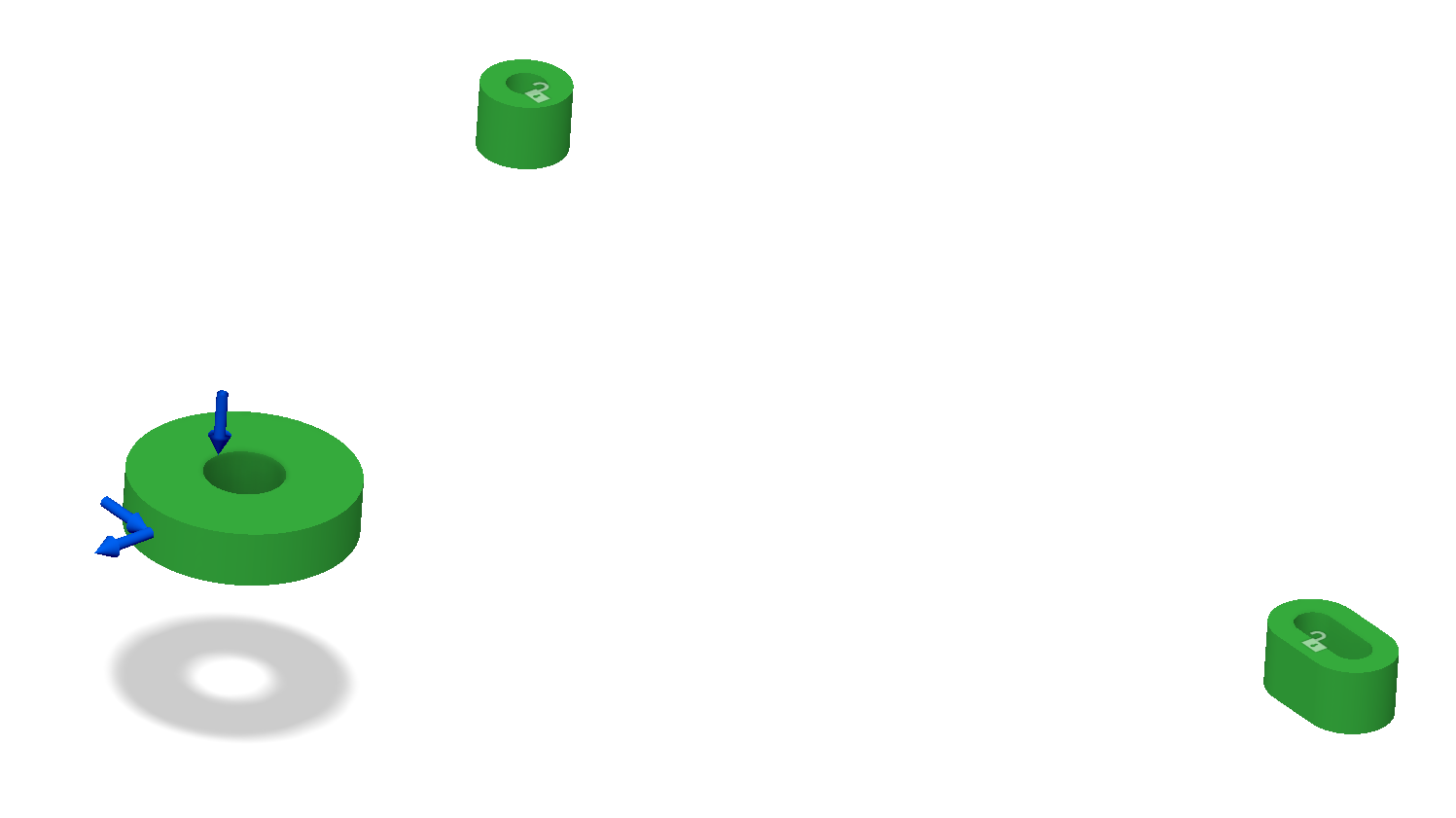

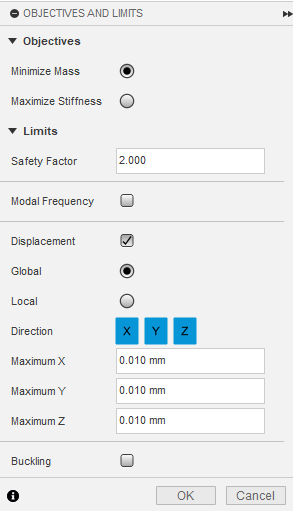

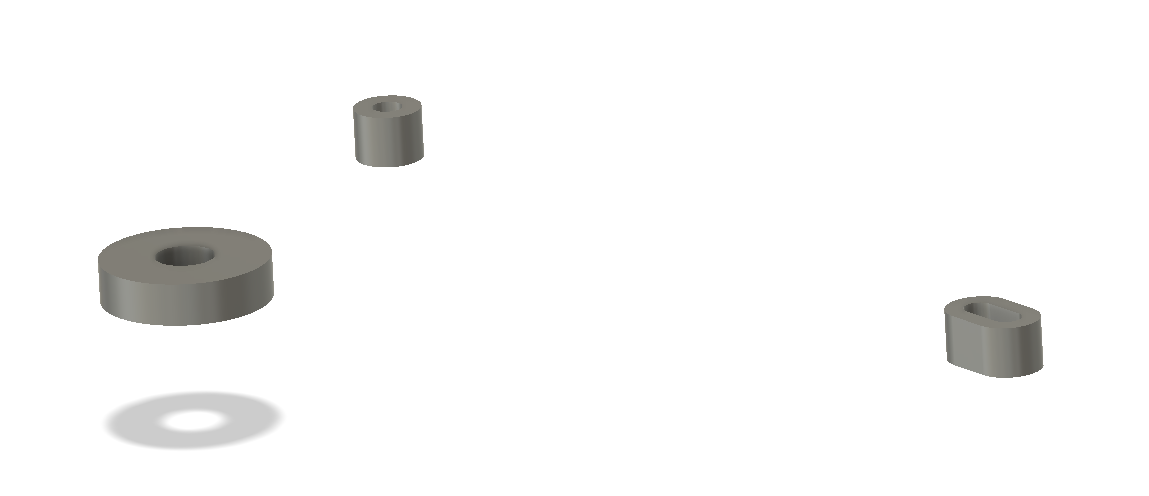

Design

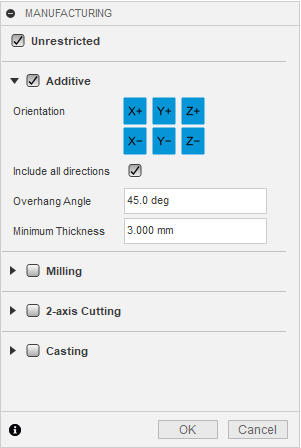

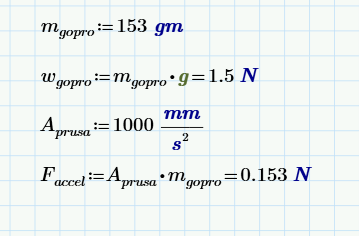

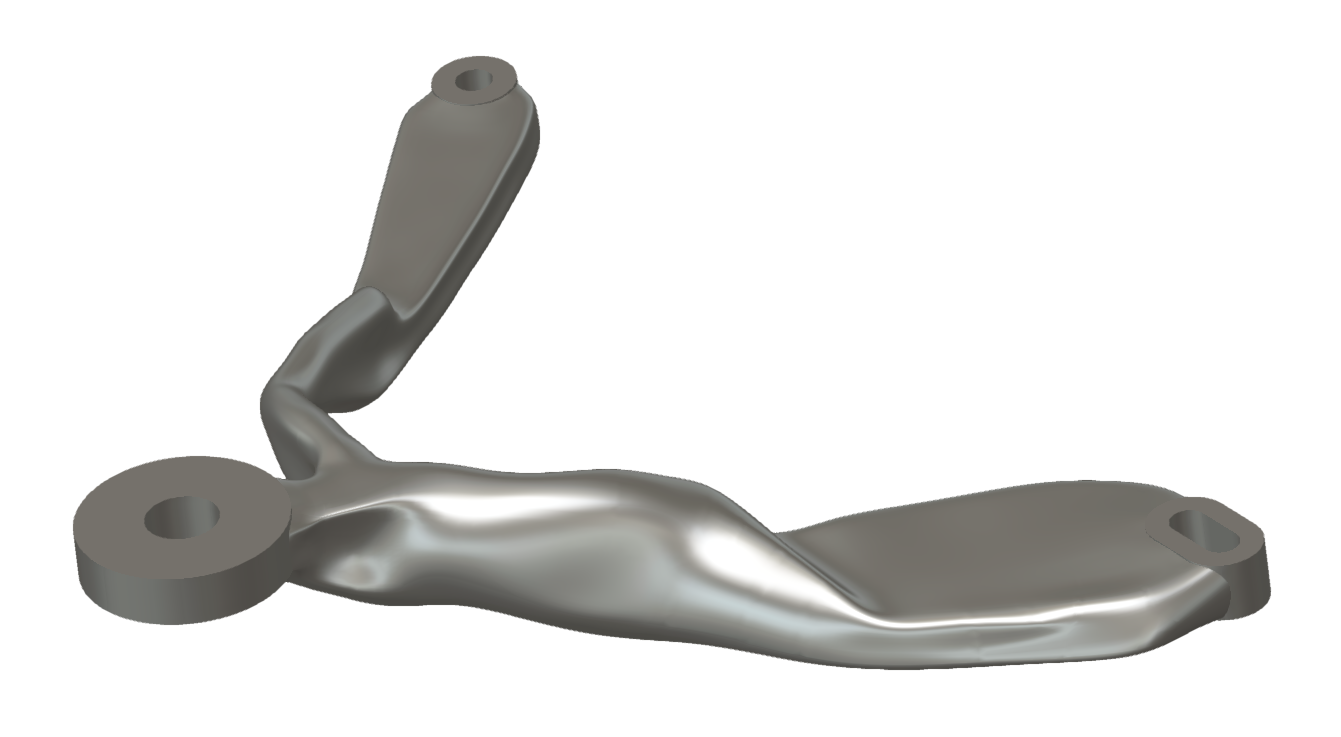

Generative design, and it’s close cousin, topology optimization, combine some form of simulation, like finite element analysis, with an optimization algorithm to produce geometries that can maintain stresses and deflections within limits while using the bare minimum of material.

What I really love about using generative design tools, in addition to the cool shapes they make, of course, is that I feel like they force me to focus time up front on defining my requirements.

Things like:

- What is attaching to what, and where. - “The interfaces.

- Do these interfaces have to have any specific features on them?, “required geometries”

- What are the loads and constraints I think these interfaces will see? - “Loads and constraints”

- Any ‘keep out’ areas for things like tool access, cable routing, or any moving parts need clearance? - “Keep out zones”

And all that kind of fun stuff.

|

|

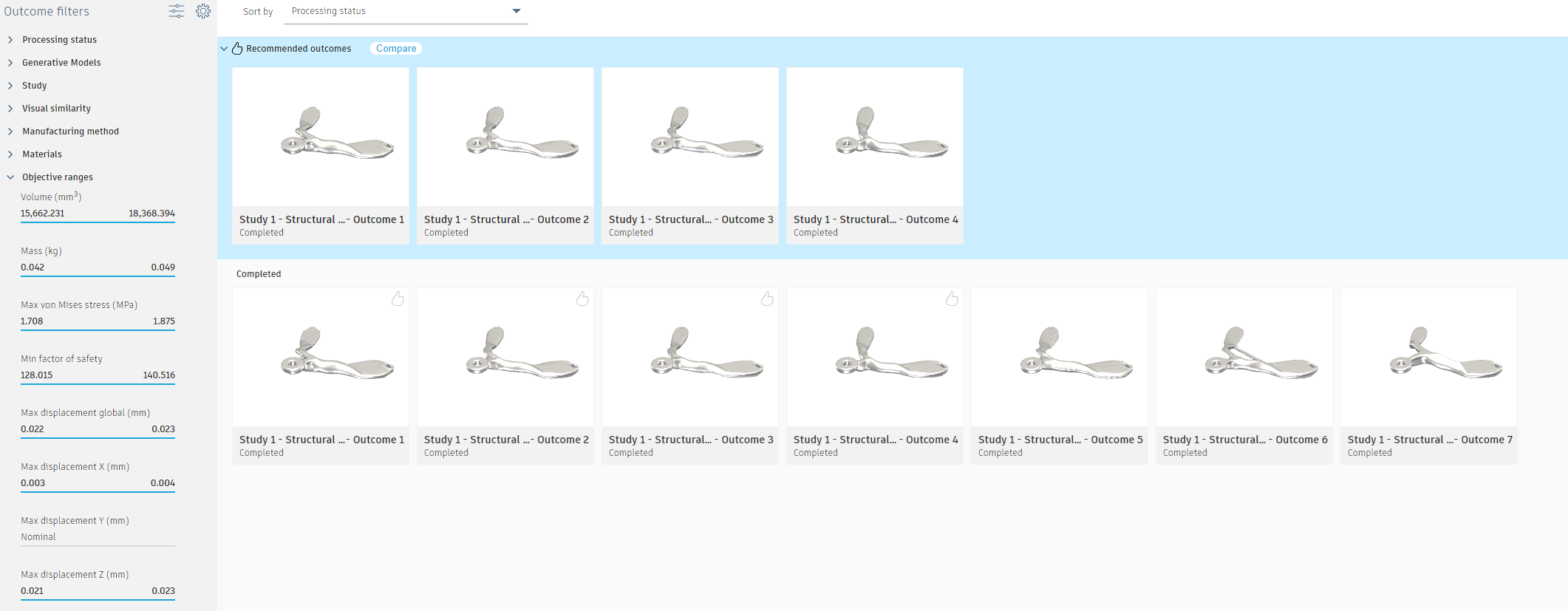

Ordering

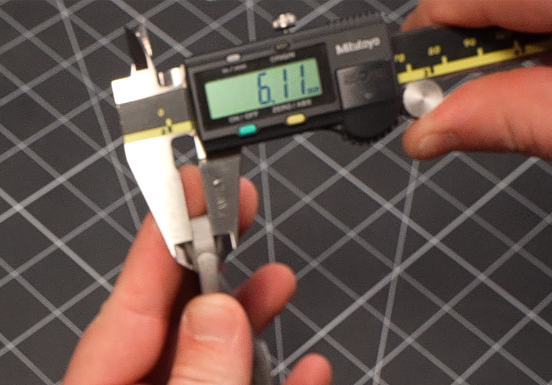

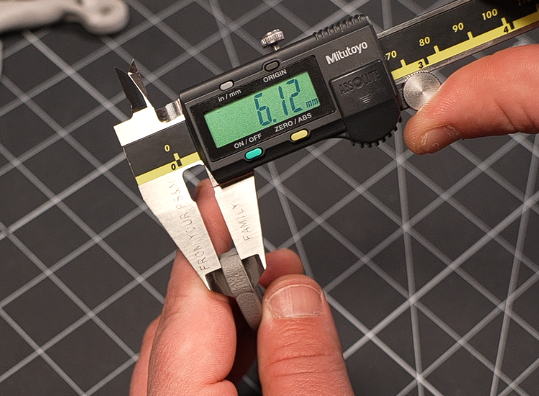

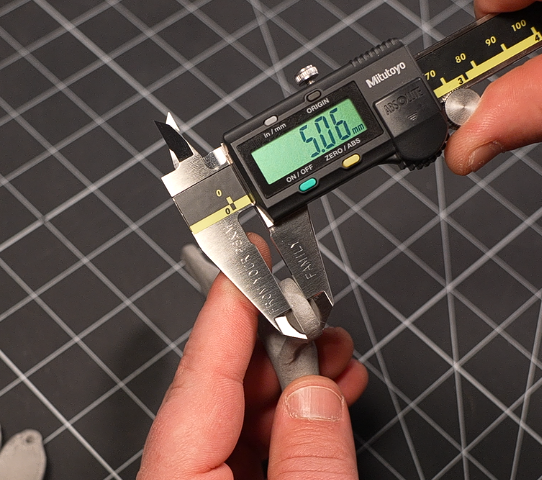

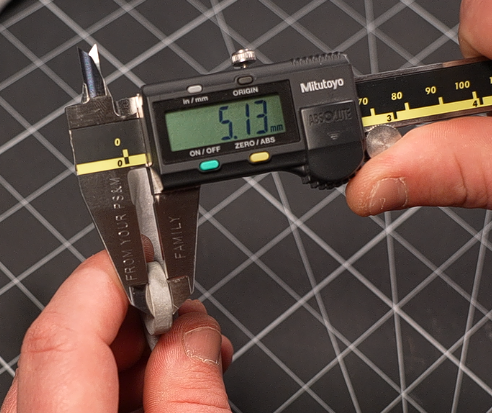

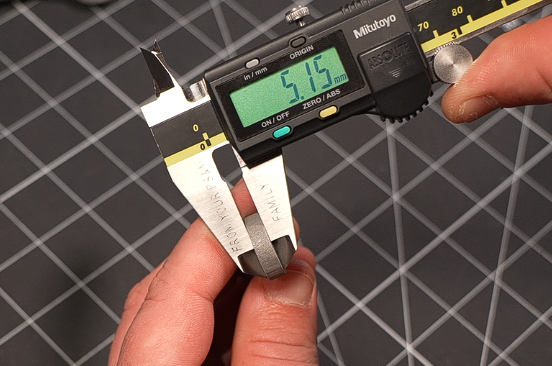

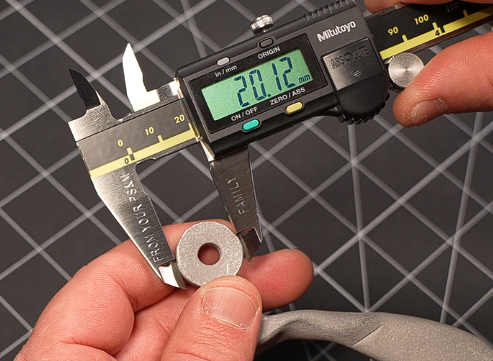

Measuring

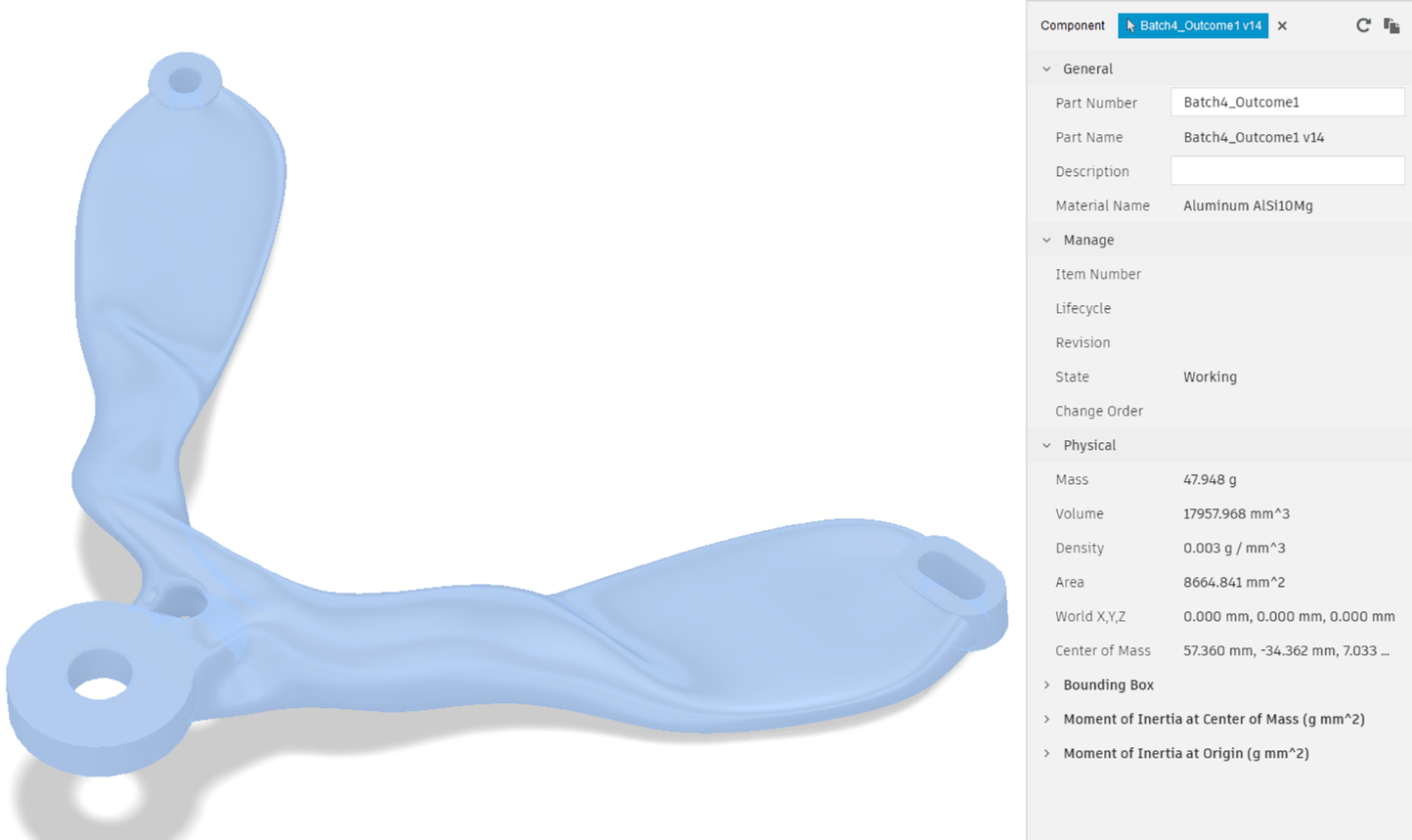

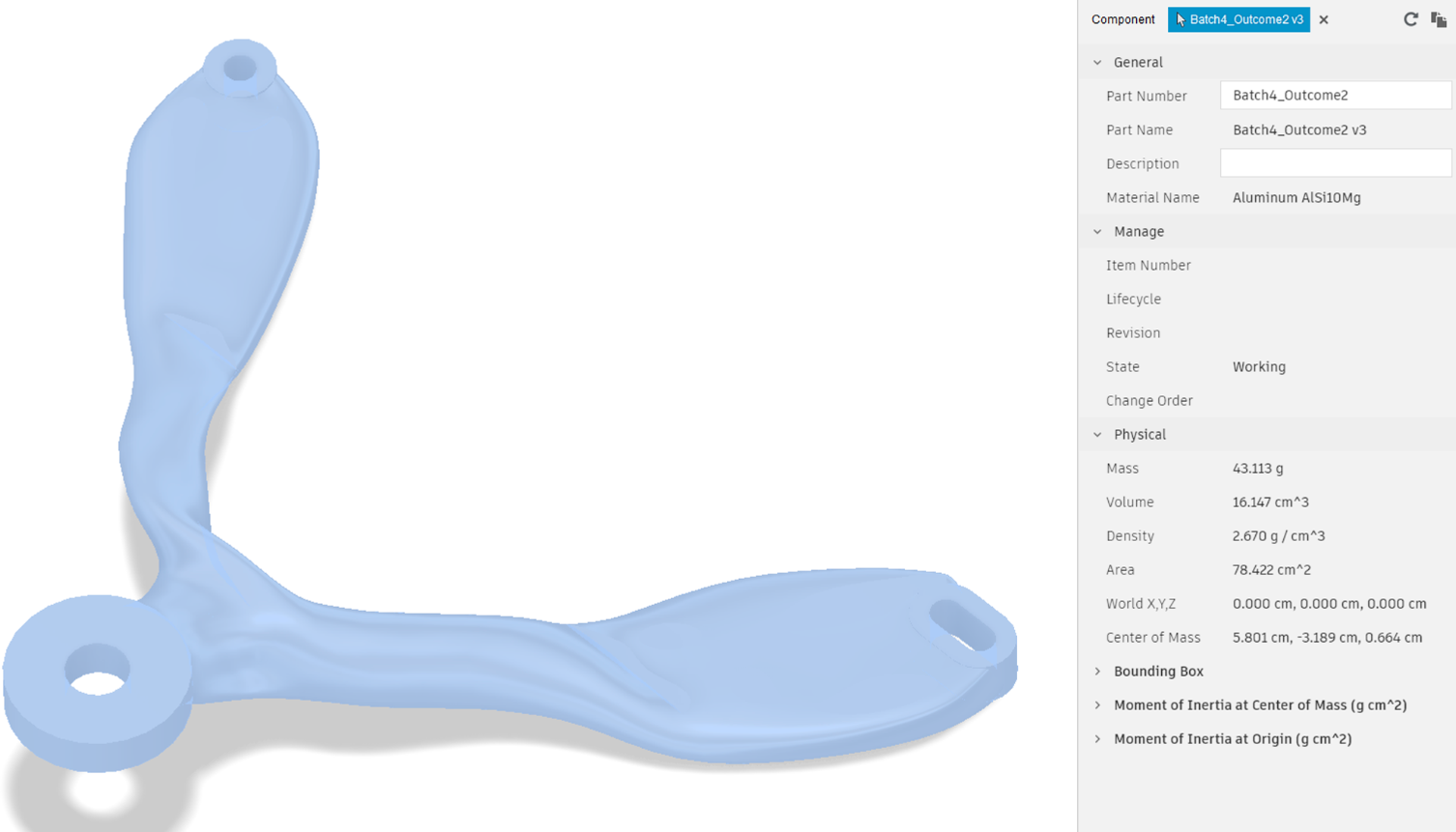

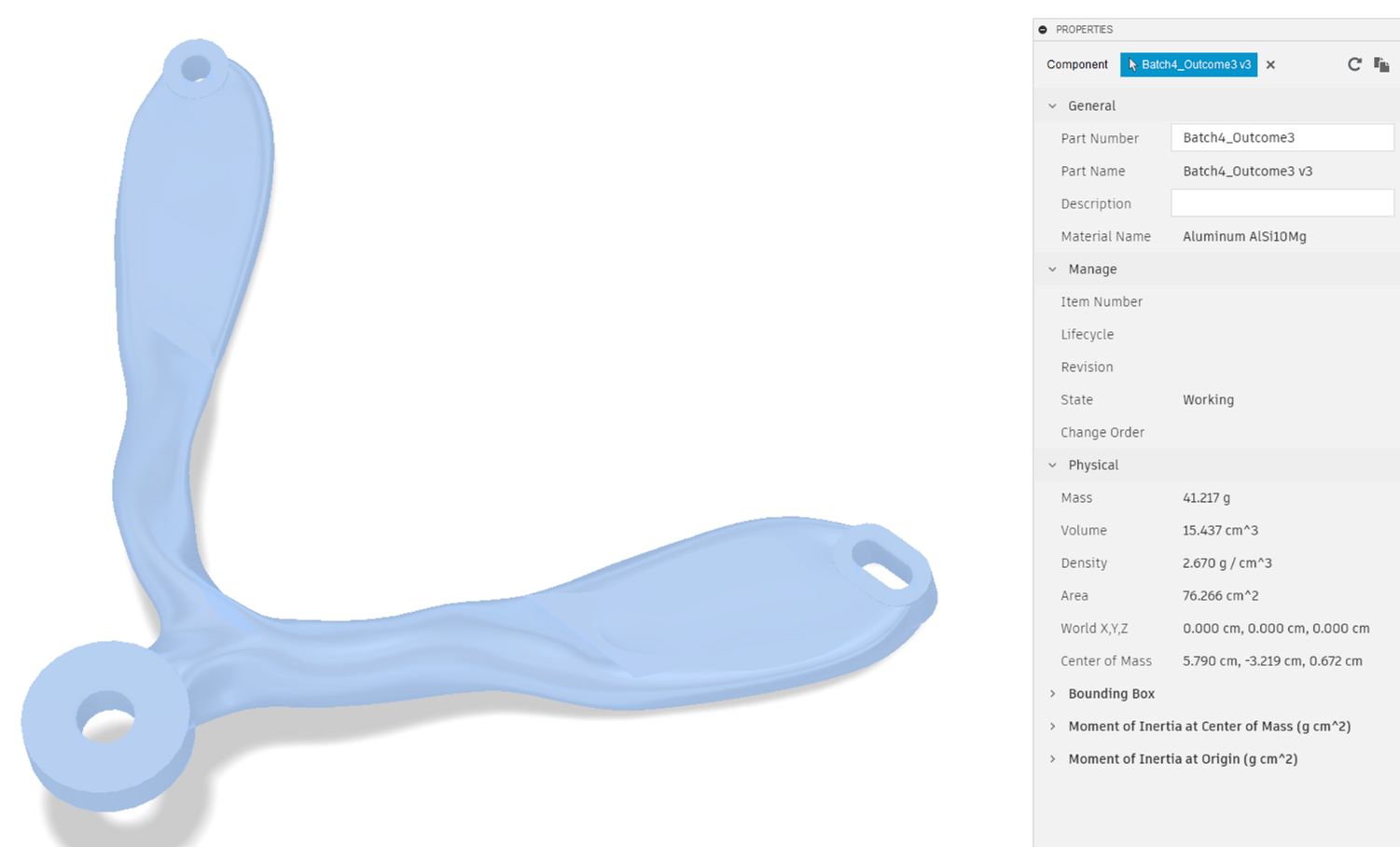

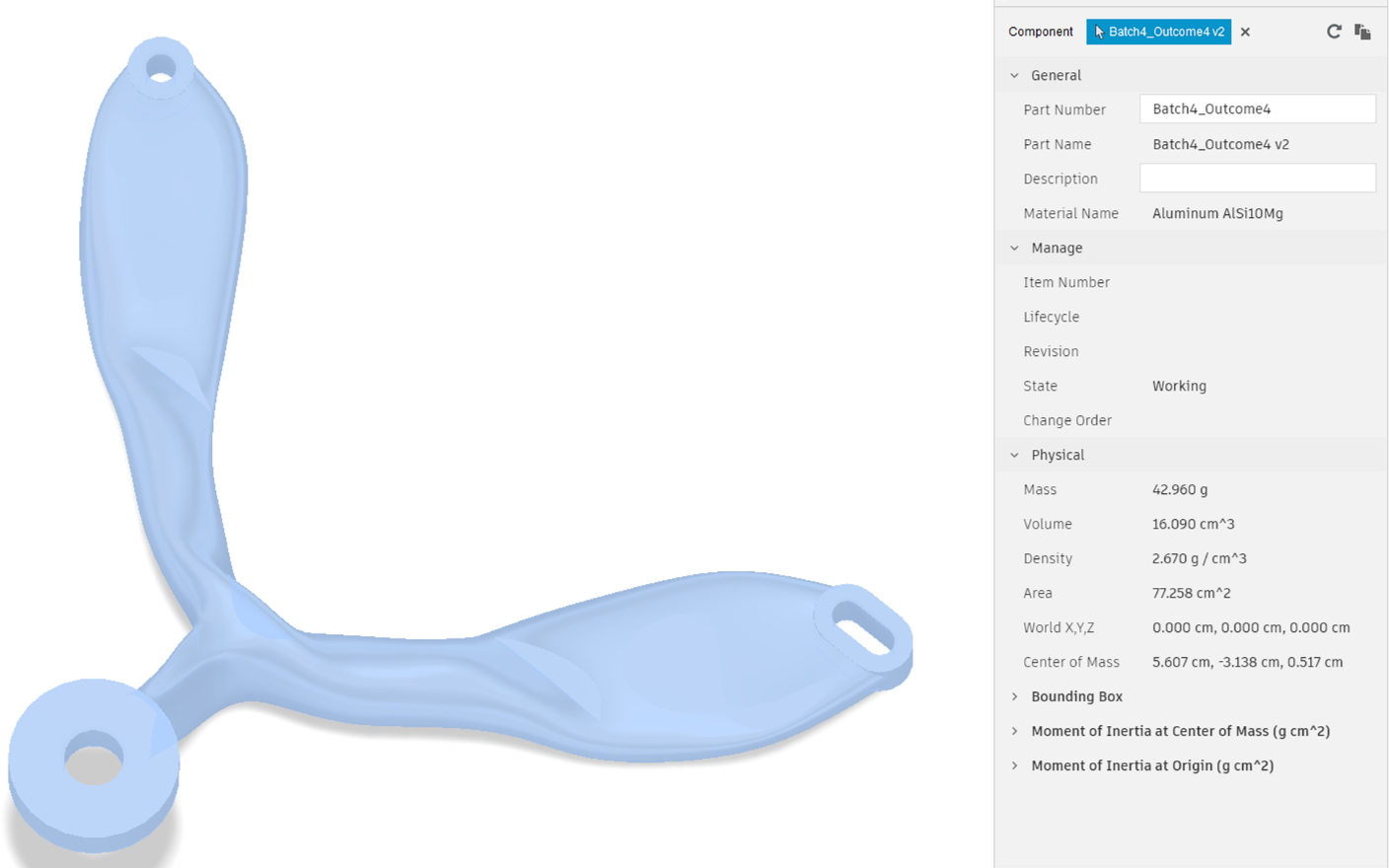

Mass

|

47.9g

|

|

|

43.1g

|

|

|

41.2g

|

|

|

43.0g

|

|

- There is not substantial porosity in the part. This does not necessarily mean that all of the powder was fully melted, but since even the high packing factor powder mixes used in these processes has a few percent void space, it does bode pretty well. Bases on the bit of deformation visible on a couple of the camera mounts, my hunch is that they have the laser powered cranked up a bit. That will give some margin on getting density, but it makes me wonder what sort of issues they may have with risidual stresses in some parts and how they're handling that.

- There is not appreciable over or under printing increasing the total volume of material.

Dimensional

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

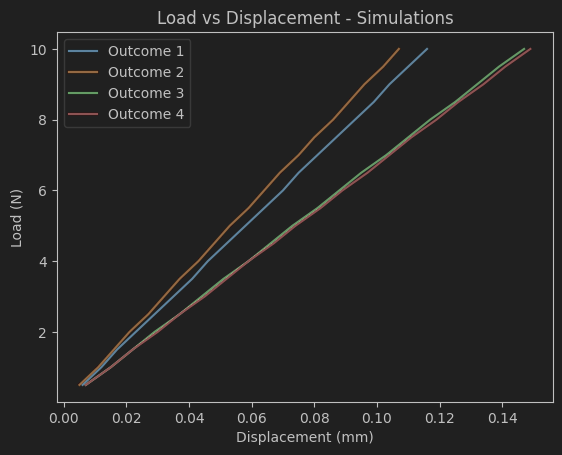

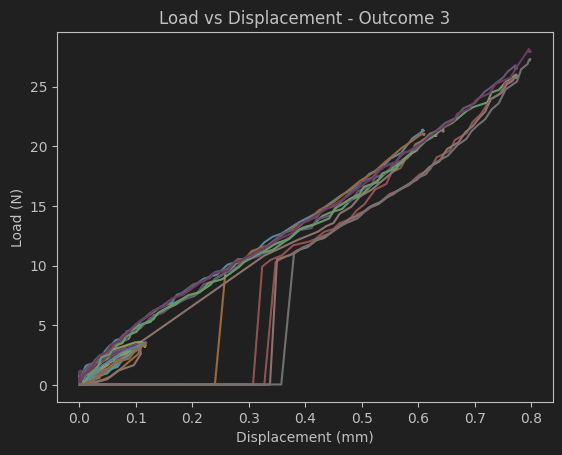

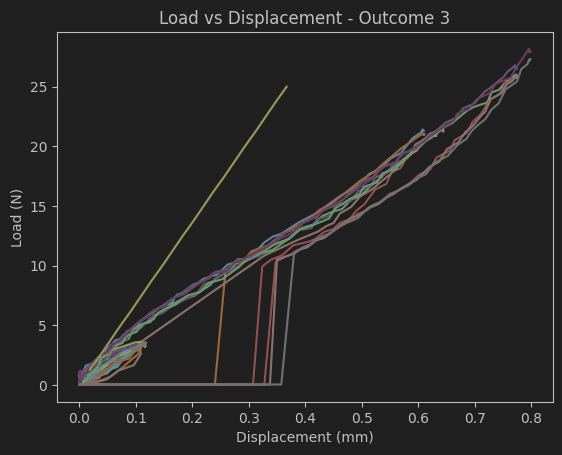

Mechanical Testing

Design Notes

2024/02/14 - Initial stab at it

- Generative Design Caliper Stand

- Generative Design SD Card (and Guitar pick, it turns out) Holder

- HydroHub - 4 in / 4 out distribution hub

- High Flow Peristaltic Pump

- Precision Dosing Pump

- Stackable/Modular Peristaltic Pump Concept

- Initial/Manual Pump

- Cam Valve - Gen3

- Peristaltic Valve - gen1

- Four Channel DrumCam Valve

Subcategories

Assorted (hopefully) "Useful Stuff" Projects Article Count: 12

Like the bucket of assorted fasteners on that bottom shelf, this category is for stuff that I didn't know how to group...oh, and speaking of those fasteners, check out the little sortin fella!

2020 Aluminum Extrusion Hardware

|

Quick Bolt Sorter

|

General Purpose Turntable - Gen1

Games Article Count: 1

Generative Design Projects Article Count: 3

During the good financial decision-making times of Covid lockdowns, etc. I decided it was a good idea to buy a license for the Fusion360 Generative Design extension...Good news, I did finally pay that off :) I had worked around, and been somewhat involved in a handful of Topology Optimization/Generative Design projects through my work, and I've found the tech super interesting for some time. So after the free trial, and feeling like I was just starting to gain some level of competence in Fusion360's tool....I done did it, and bought the year. Ok, now that I'm done justifying that to myself...I mean you...

<engineering/design> What I really like about Generative Design is that it forces the designer to think about the thing they are trying to design from it's core requirements: Forces, Interfaces, and Keep Outs. I think it's far from perfect, especially given the still very primitive Design For Manufacture capabilities these tools have (among other shortcomings, but this one is certainly a big one to me.)

<precision engineering> One last also (for now), but ALSO, what I find exciting about these tools from a precision engineering perspective, is that the above-mentioned focus on forces and interfaces, these tools are extremely well-suited to kinematic/exact constraint designs! I think every one of the Generative Design projects below features at least some aspects of kinematic constraint (I say, "I think" because I may or may not be writing this before I go through my files and remind myself what all I actually made vs what I just thought about making ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ )

JFS Projects Article Count: 14

AgTech (aka finding a way to complicate and digitize gardening) Projects Article Count: 12

Hydration and Hydroponics Projects Article Count: 8

Peristaltic Pumpin Article Count: 4

A lot of projects I work on/have worked on seem to involve the controlled movement of fluids. Below is a bit of a history of my builds involving attempts at obtaining this controlled movement for incompressible fluids. I haven’t done much myself with making custom solutions for the compressible stuff, but if you’re interested in such things, I thoroughly enjoy Major Hardware’s “Fan Showdown” series :)

This article/section is by no means intended as a thorough overview on the design and operation of pumps. While I will try to give some overview on operating principles and design considerations as I go, this is mainly just going to be a wander through my personal builds and experiences.

Peristaltic Pumps

What is a peristaltic pump?

I’m sure there are innumerable sources online for (much better) detailed discussions of the workings of peristaltic pumps. So I’m just going to hit the highlights, and I’ll try to remember to find some promising links and add them below, should a deep dive seem intriguing to ya.

Basic Operation:

The fluid being pumped is carried into the pump in a compliant tubing. This tube is routed around some portion of a circular/cylindrical path around the axis of the pump and then exits the pump. This is one interesting/attractive aspect of peristaltic pumps, the fluid never has to leave the tube that it is in, making these pumps well-suited to situations where contamination and/or leaks are highly undesirable. The housing that features the cylindrical wall that the tubing is being routed along can be considered the Stator, and that is generally the nomenclature that I tend to use.

So if there’s a Stator, there must be a Rotor…? Yup, the rotor includes some set of features that extend out to some defined gap between this feature and the Stator wall. These features, which in many peristaltic pumps are rolling element bearings, pinch the tubing to the point of sealing (ideally) the tube. As the rotor turns, this contact point proceeds around the circumference. Because the pinched point of the tube is sealed, the volume of fluid in the tube ‘ahead’ of the pinch point are, as a result, pushed forward. So, keep rotating, keep pushing….pretty much as simple as that!

Pros:

- Positive Displacement Pump

- Because the pinch point is (ideally) fully sealing the tubing, the amount of fluid moved is directly proportional to the movement of the pump. This makes them very good choices for things like dosing pumps or other applications where the desired volume of fluid to be moved needs to be deterministic.

- This is a large driver for my initial interest in using peristaltic pumps. Their deterministic flow is/was very attractive for my plant growth experiments. They can give very repeatable watering volumes and nutrient concentrations.

- Fluid Isolation

- Because the fluid never leaves the tubing, these pumps can be suitable for moving hazardous materials. For example, I have been using a peristaltic pump for transferring 99% IPA

- Relatively Simple Construction

- Because the fluid does not have to be sealed within the pump, these pumps lend themselves well to DIY builds. No shaft seals, gaskets, etc. or complex (at least to do well) impeller design needed.

- Self-priming and Head height

- If well-sealed, these pumps are capable of self-priming (and even pumping air) and of achieving pretty impressive head heights (the measure of how high above the pump it can pump a column of water)

Cons:

- High drive torque

- Because of the preloading needed against the tubing, and the rolling friction, even with good rolling elements (more below on this), it can be quite easy to end up with designs that require quite a lot of drive toque.

- Tubing wear

- With the relatively large deformation and high number of cycles, the tubing will eventually fail, either due to material wear, fatigue cracking, or who knows what else. Because this failure mode can cause fluids leaking into your pump not designed to experience this fluid, this failure can potentially be quite problematic. So the use of high-quality tubing material and a plan for periodic maintenance, are worthwhile.

Test Build 1

A couple of years back, I had a concept for an in-line-mixing hydroponics system. The idea being that the supplies to the system would be just pure water and nutrient concentrates, and a series of pumps and valves would allow precise dosing mixes to each target plant in a system (I refer to this concept as Rail Yard Hydro, since it moves the fluids around the tubing network quite like rail cars are moved around a rail system. I’m planning to add a separate page diving into that one a bit deeper since it is the design scheme I am using in my current projects.)

Well, to facilitate this plan, I wanted to find an option for a dosing pump that I could integrate in to my control system (aka Arduinos and Raspberry Pi’s :)). Unfortunately, I quickly found that a servo-driven peristaltic pump could easily set me back north of $100….so I set out to spend many multiples of that making my own!

Actually, when I saw the pricing, I decided I should see if I could make myself a cheapo, manual version that I could use to just test out some basic questions on the Rail Hydro idea (mainly verifying that I could induce good material mixing in-line and that there was no cross-contamination between fluid reservoirs.) And so, ‘twas this endeavor that resulted in the pump I’m apparently referring to as “Test Build 1”

Design Objectives:

- Be a peristaltic pump

- Provide a full seal (at 100mm head)

- Be hand-cranked

- Not require any parts that would have to be ordered (I’m impatient)

The Build

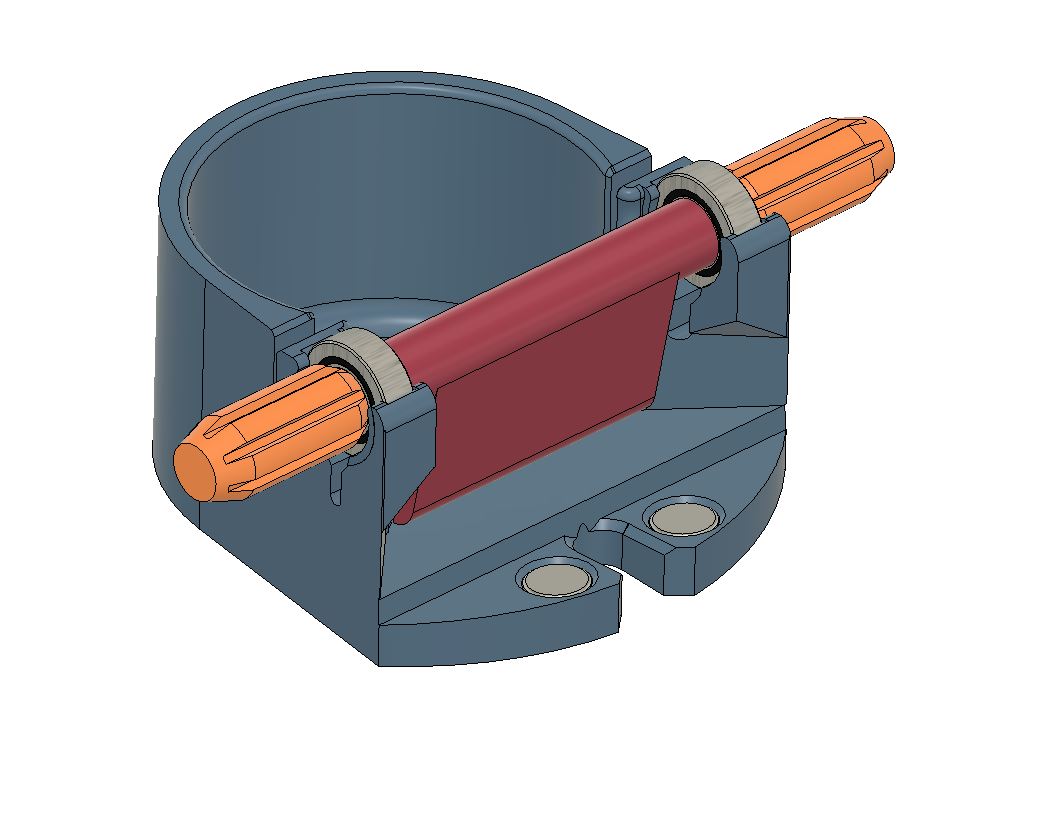

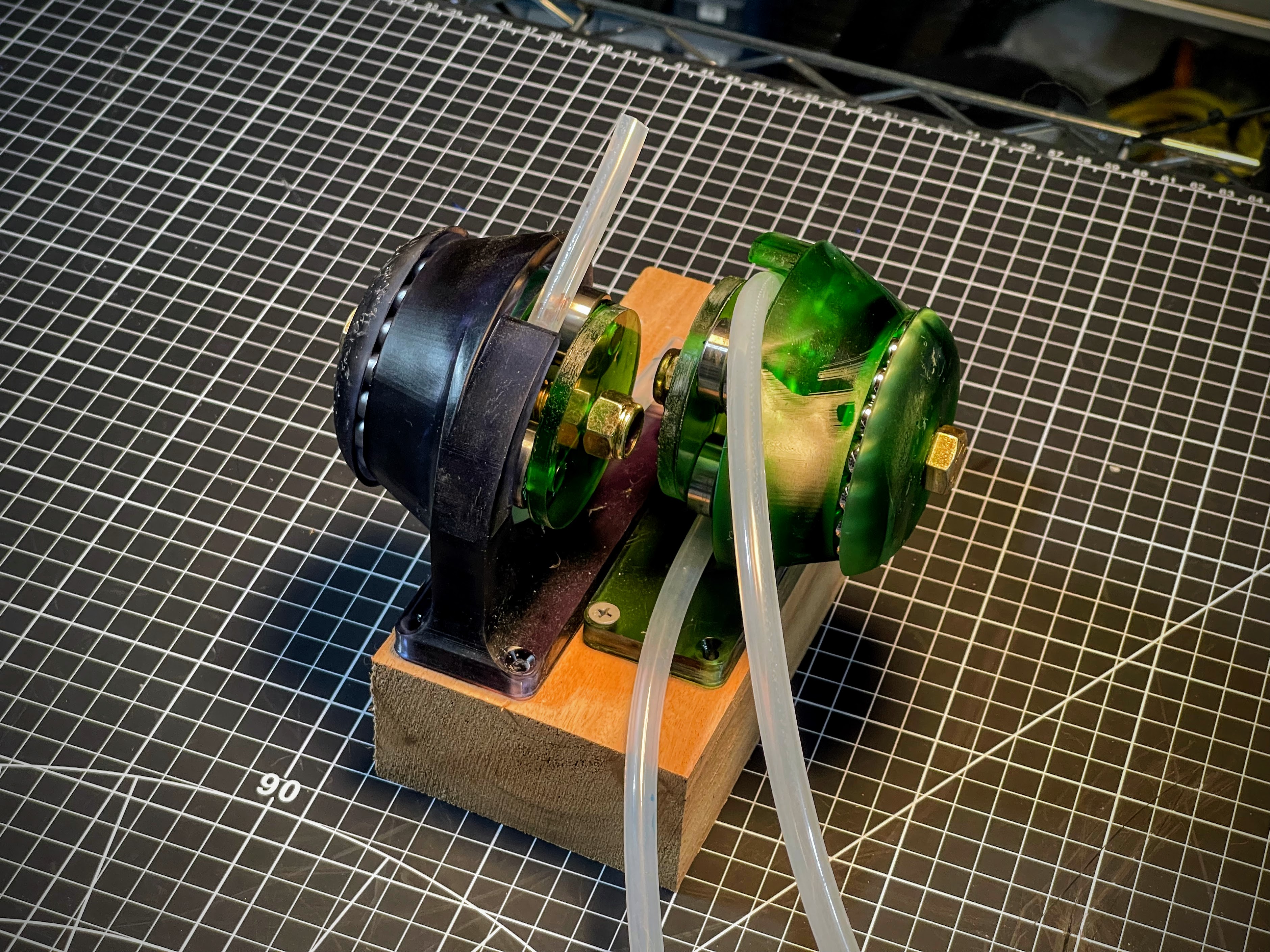

She ain't pretty (especially after a good while of getting knocked around), but the pic above shows the dual pump setup I rigged up for my testing needs. I was VERY pleasantly surprised that, other than a tweak to the hand wheel, these things worked pretty damn well!

I decided upfront that I was going to go with a resin printed build, because I thought the high stiffness and good surface finish throughout the 'pinch region' would give me a better chance. Since I was already going to have the good surface roughness, I might as well also integrate the main bearing into the printed parts.

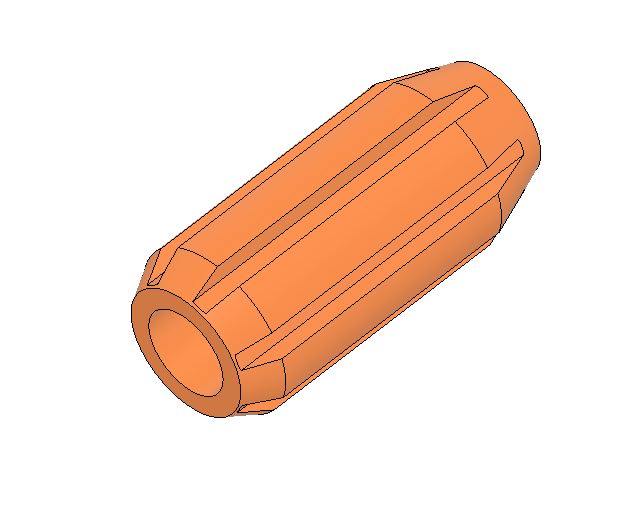

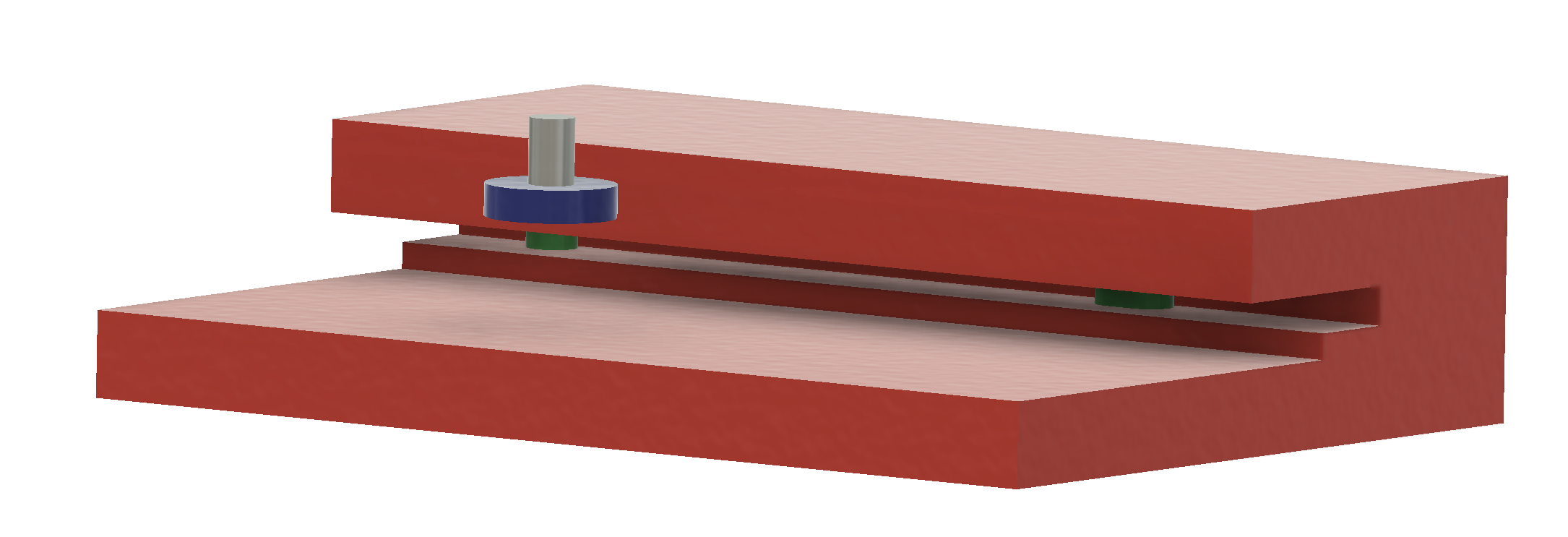

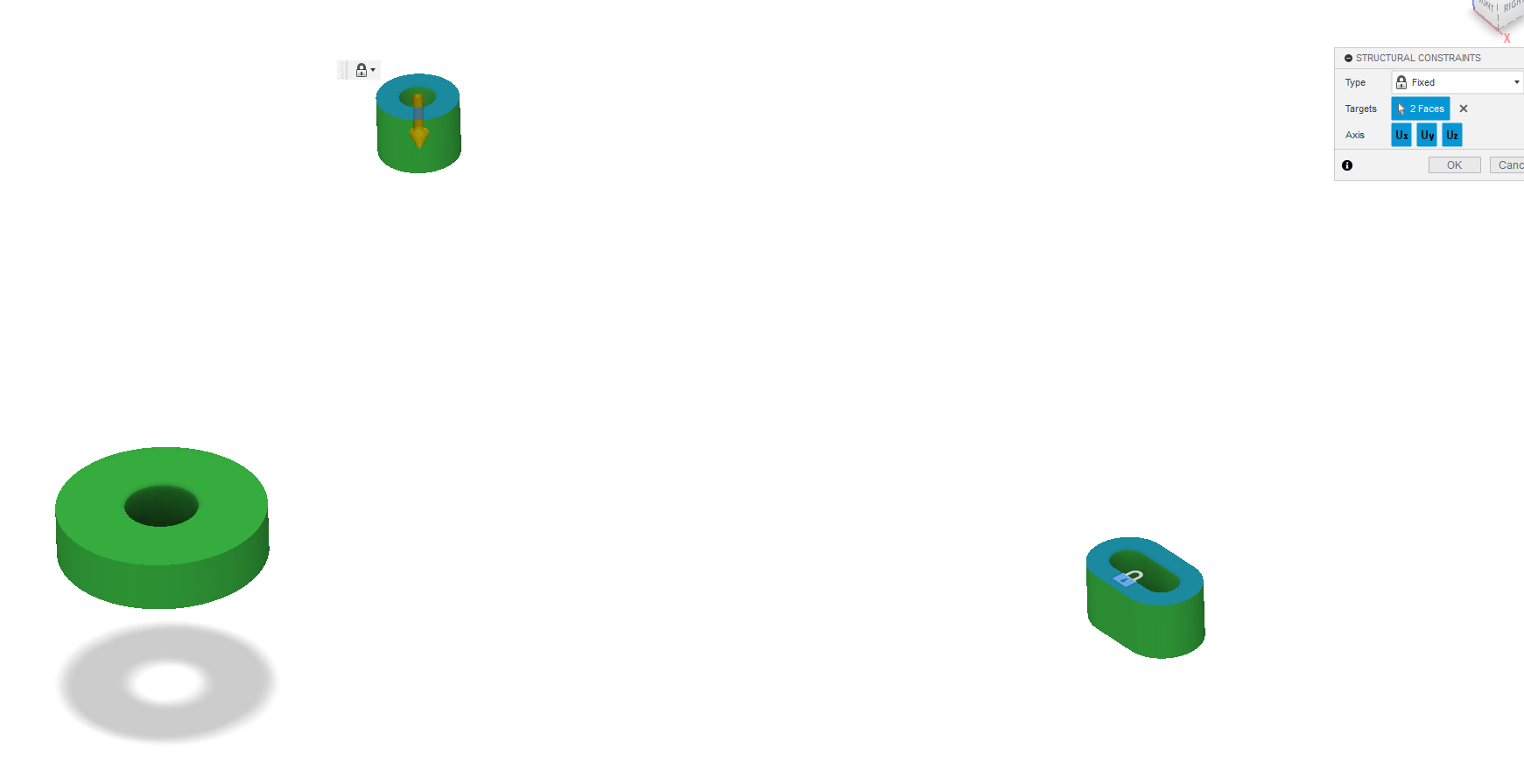

In the image of the model, below, the Stator is the part shown in green, and the Rotor is shown in blue(ish.) Riding on the rotor are roller skate bearings to provide the contact with the tube. Race 1 has v-grooves on both sides of the race, providing the main constraint for locating the rotor, and Race 2 has a v-groove on the Stator, but only a single plane of contact on the Rotor side. This keeps from over-constraining the bearing.

|

|

The absurdly overkill bolt running through the center is a real showcase of "using what I had on hand" :) in that these were the only bolt/nut sets I had on hand with the length I was looking for.