Just Playin and Concept Demo Projects

- Details

- Parent Category: BubsBuilds Projects

- Category: Just Playin and Concept Demo Projects

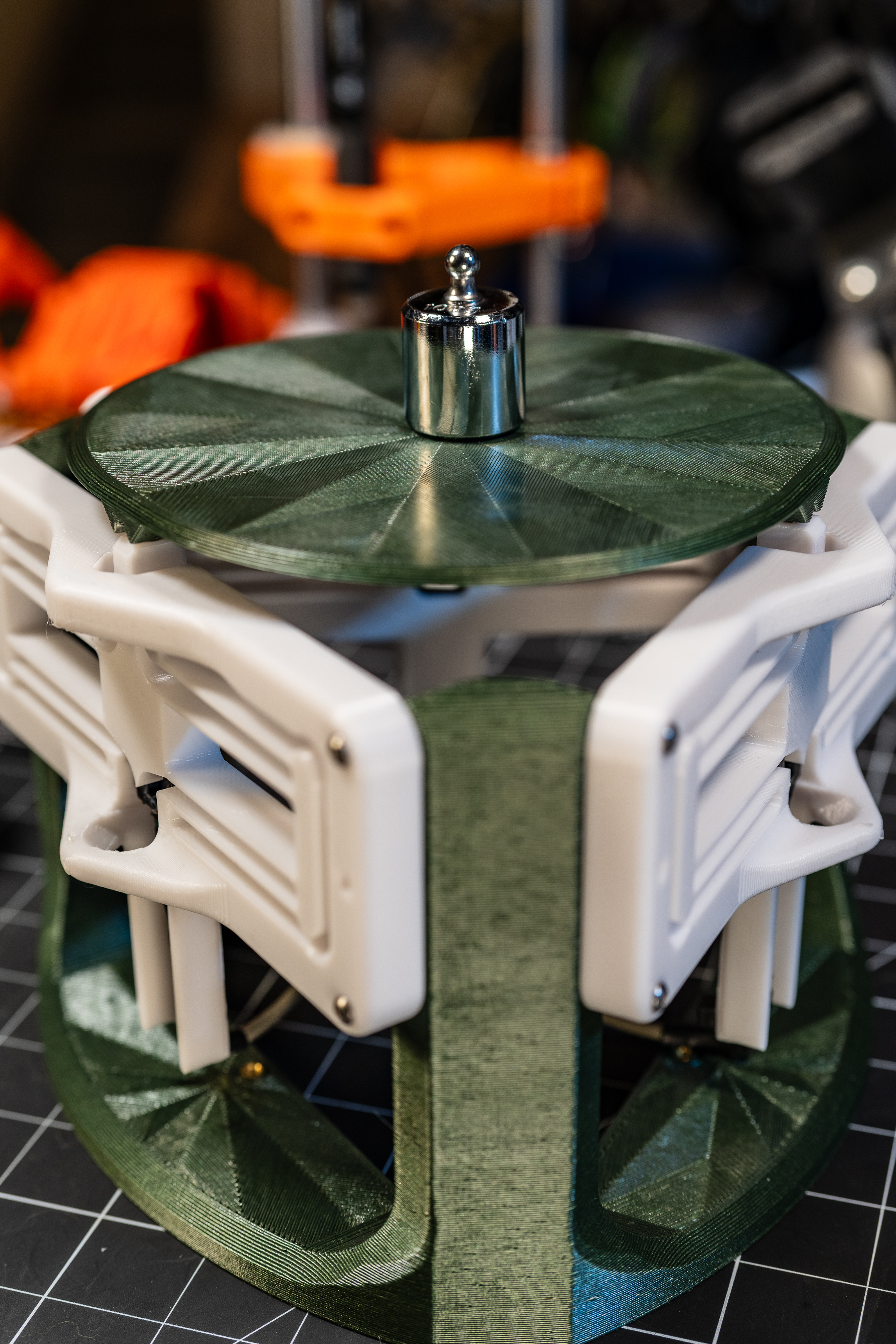

Ummm, yeah...so I'm just gonna upfront admit that this just plain didn't need to exist, and isn't even particularly successful...I mean, it holds paper towels, so I guess it's "successful"...anyway

|

|

So the motivation here was that I got frustrated when I pulled a paper towel and got the whole roll, and but five minutes later, I pulled on the toilet paper roll only to be granted one square at a time. Clearly this wrong needed righting through improved dynamics, or somethin. I decided if I could crank up the damping (the velocity-dependent resistance), then the dispenser would basically pull back proportional to how hard I yank the paper, or at least that's the idea.

Key features/phrases to make it sound impressive:

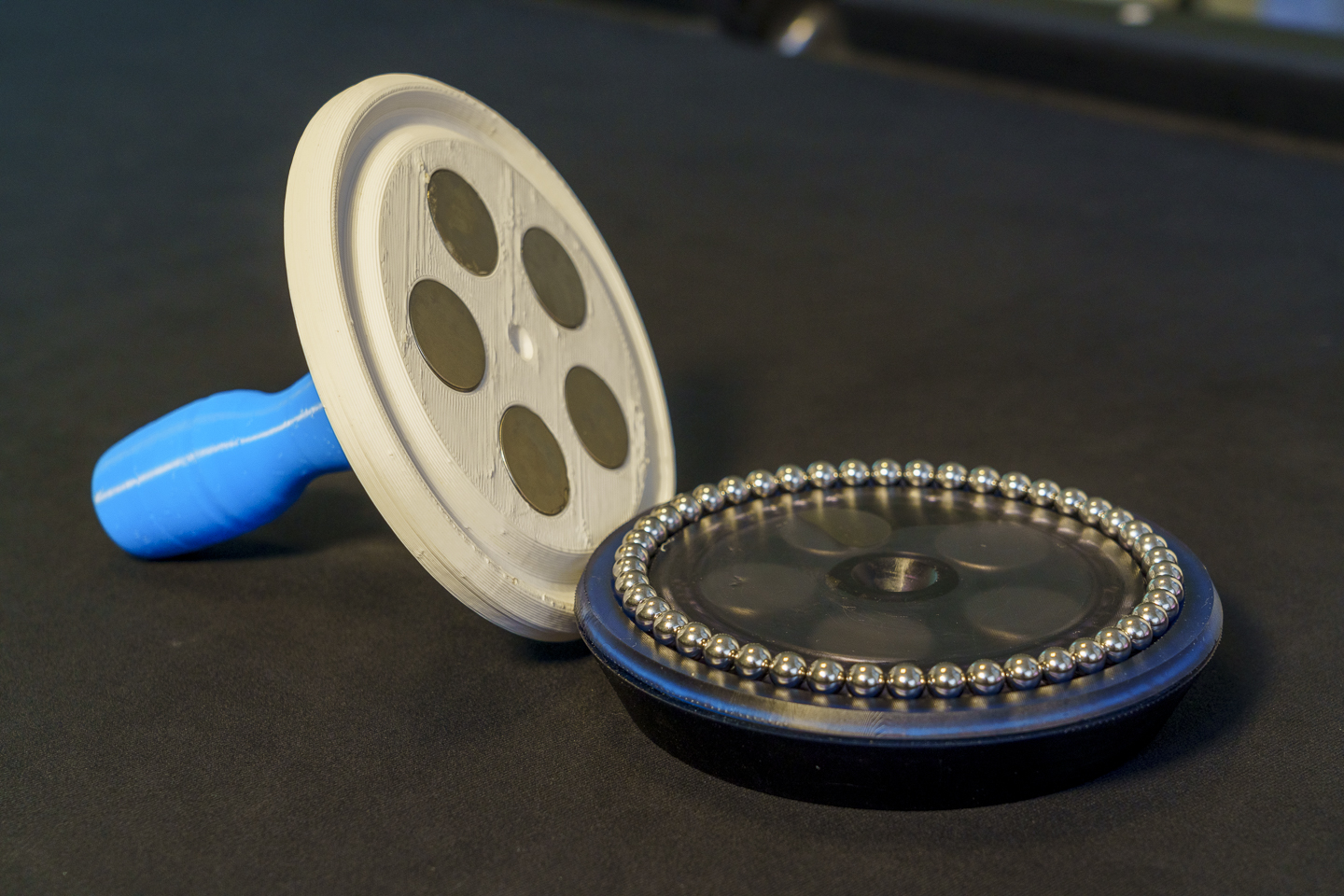

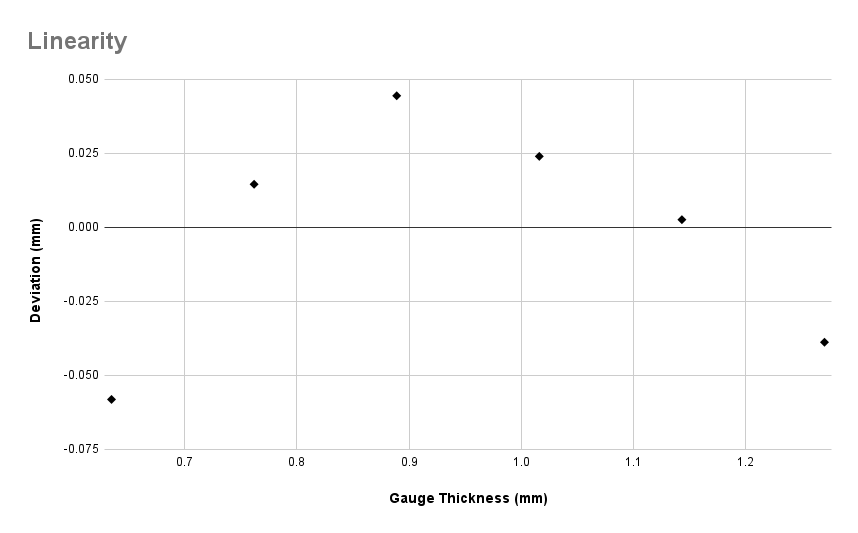

- Base contains a magnetically-coupled fluid damper

- The base itself has an integrated stator and locating features/bearing races for the rotor

- The magnetic coupler between the rotor and the turntable also provides the preload for their respective bearings (and hold the thing together)

- The base is sealed with a printable TPU gasket

- Paper towel is 'secured' to the holder with the compliant, TPU post.

Soooo, I'm not really expecting anyone to do as I've done, and build one of these things, so I'm not currently planning to include a step-by-step build for this. But, if I'm somehow wrong, and you'd some more info, drop me a comment on Printables or the like...and I'll very much consider it :)

But here's a quick overview of the parts:

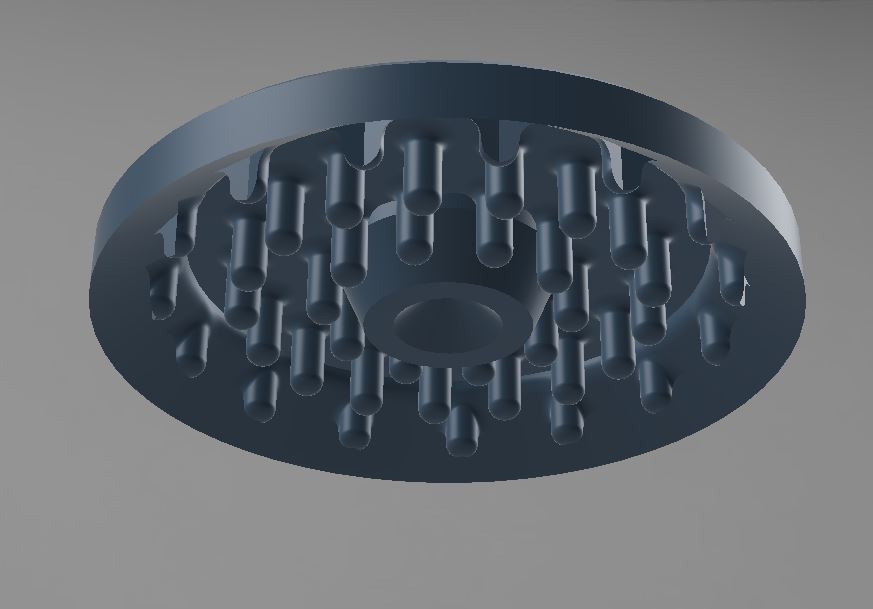

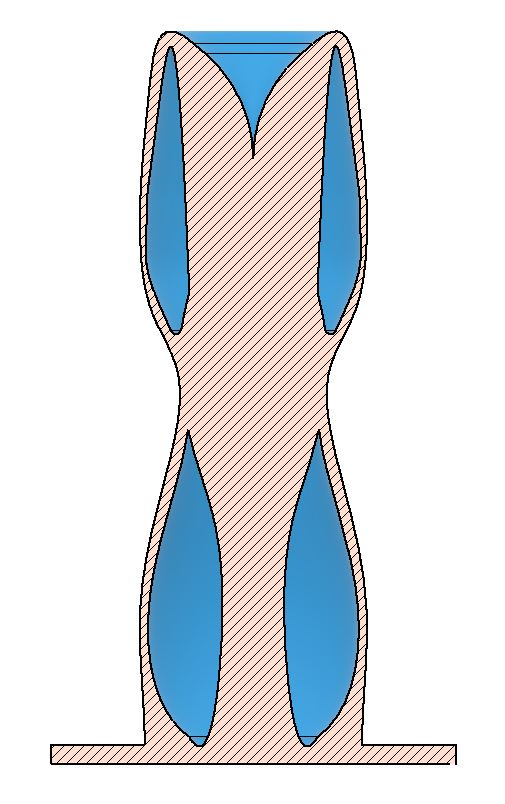

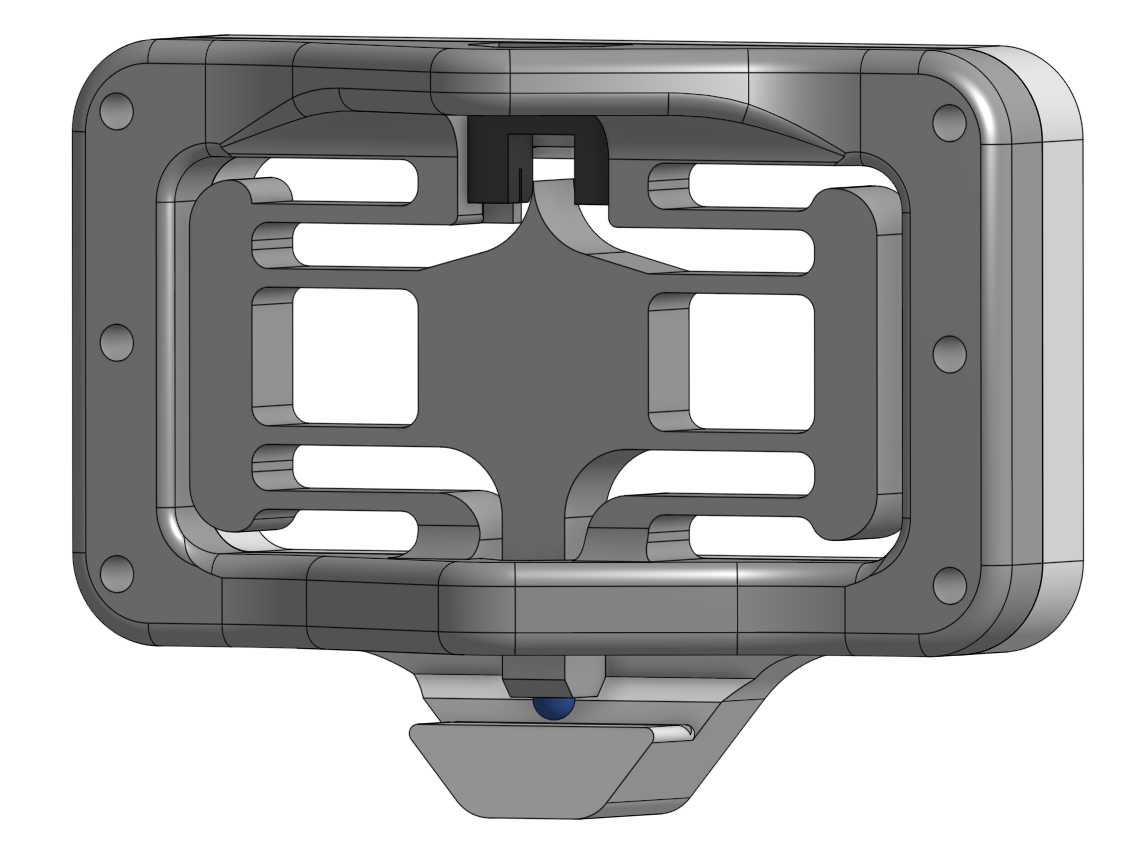

Base/Stator

The posts arranged around the middle are there to create additional drag in the working fluid and increase the damping. The grooves around the perimeter are for the gasket and adhesive to seal it up. And the cone cutout in the center is for a "jewel bearing" that locates the rotor and is...get this...a bearing :)

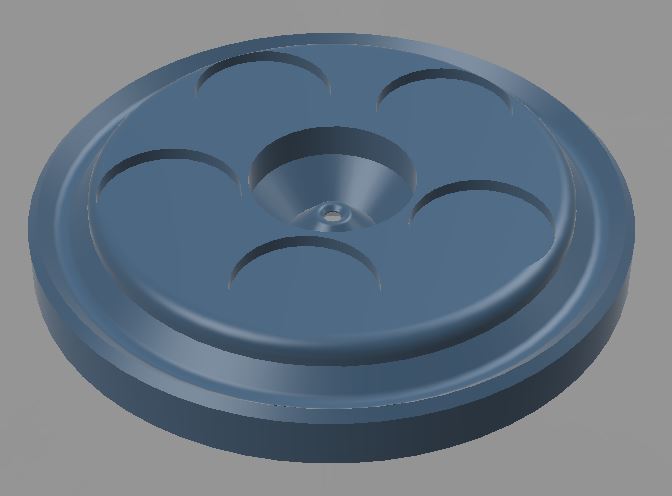

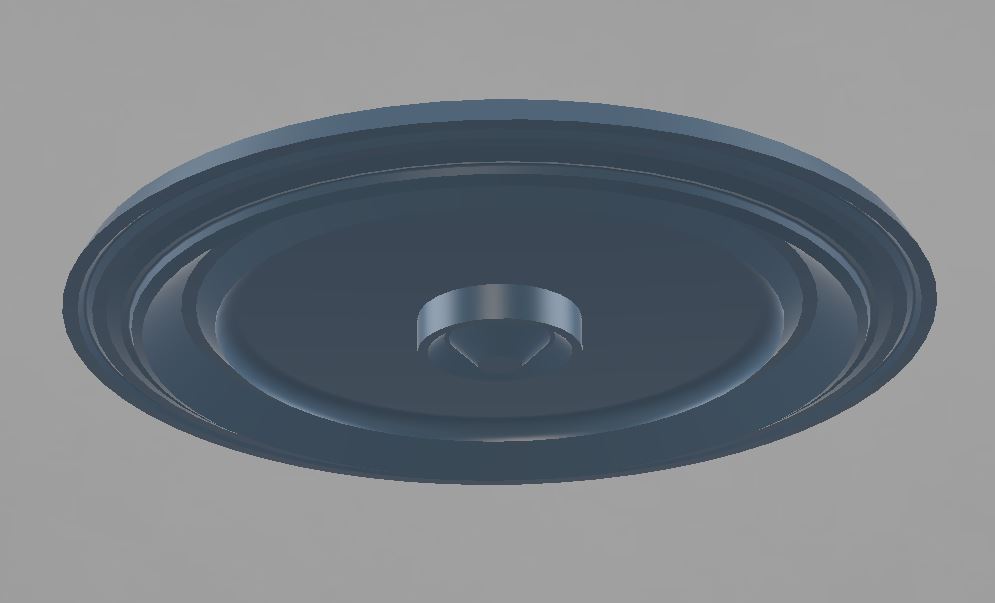

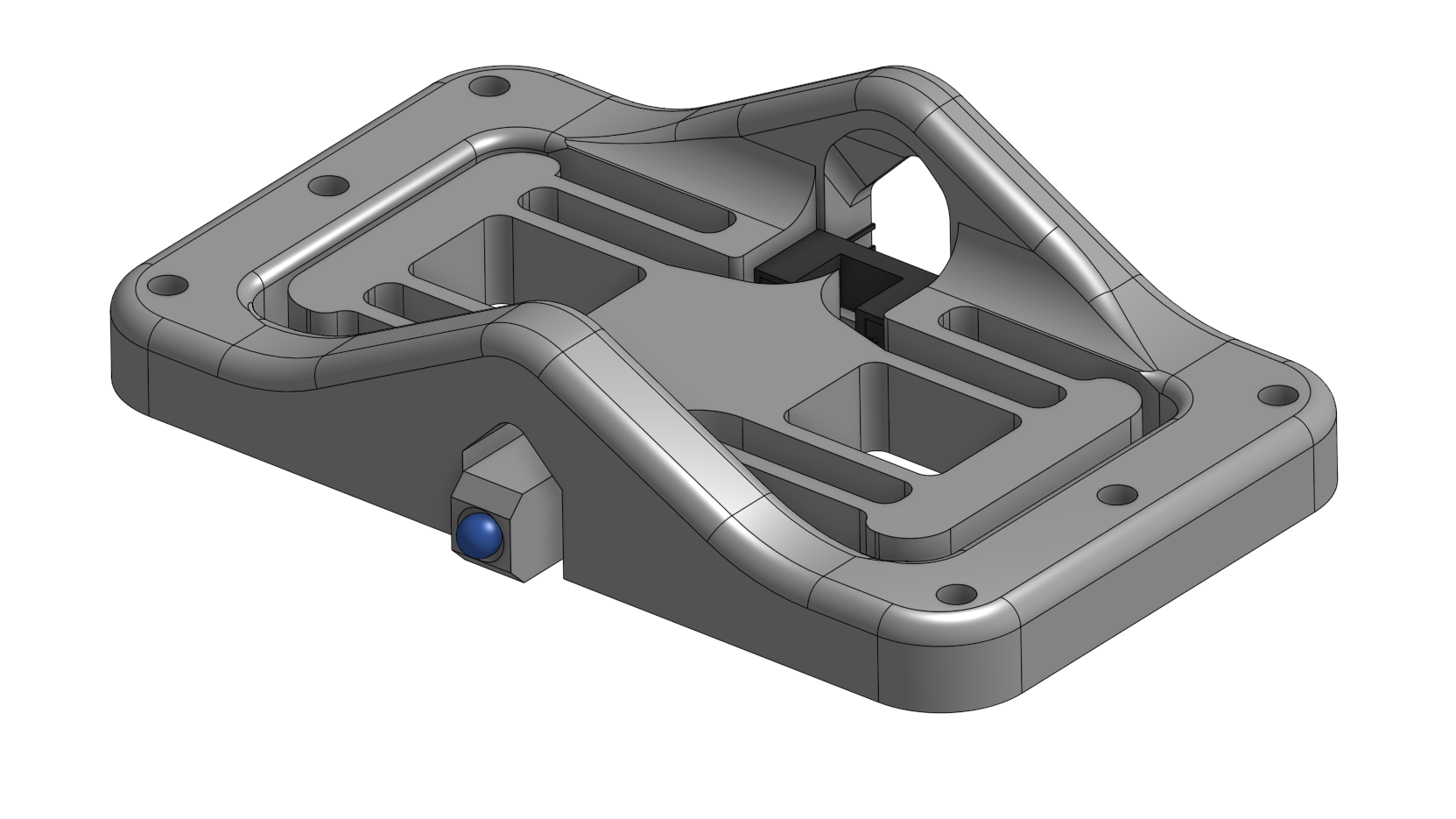

Rotor

|

|

The bottom side of the rotor (image on the right) includes the mates for the above-referenced drag posts and jewel bearing. On the top, the five large cylindrical pockets are for the magnets that will do the coupling. And in the center and around the perimeter, more bearing races.

NOTE: on the bearing races on the top of the rotor, this is over-constrained, but I was worried about possible deformation in the rotor due to the magnets, and didn't want to risk the posts colliding. However, I think there is likely sufficient stiffness in the rotor to leave the inner race empty. So you'd only use the one jewel bearing on the bottom (with a single large ball) and the outer ring of 3/8" balls.

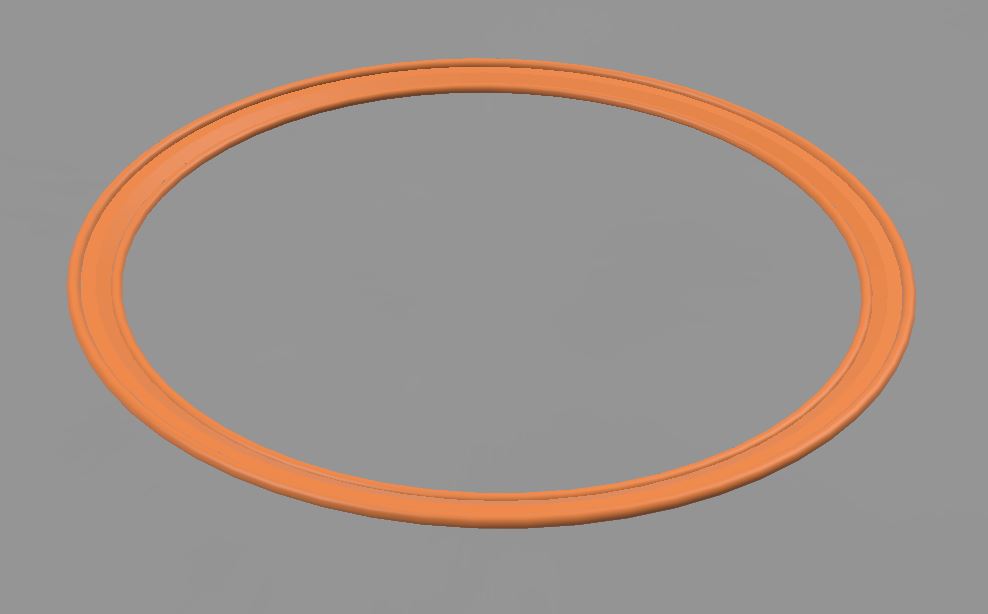

Gasket

The gasket is not intended as a stand alone seal, as the intent is/was to bond the shell together using a waterproof adhesive (like Goop...actually Goop, I used Goop). So the idea is to print the gasket from TPU, and lay beads of Goop in both of the flat regions. This has seemed to hold up great for mine. It's been about a year since I first built this and it hasn't lost a drop of oil.

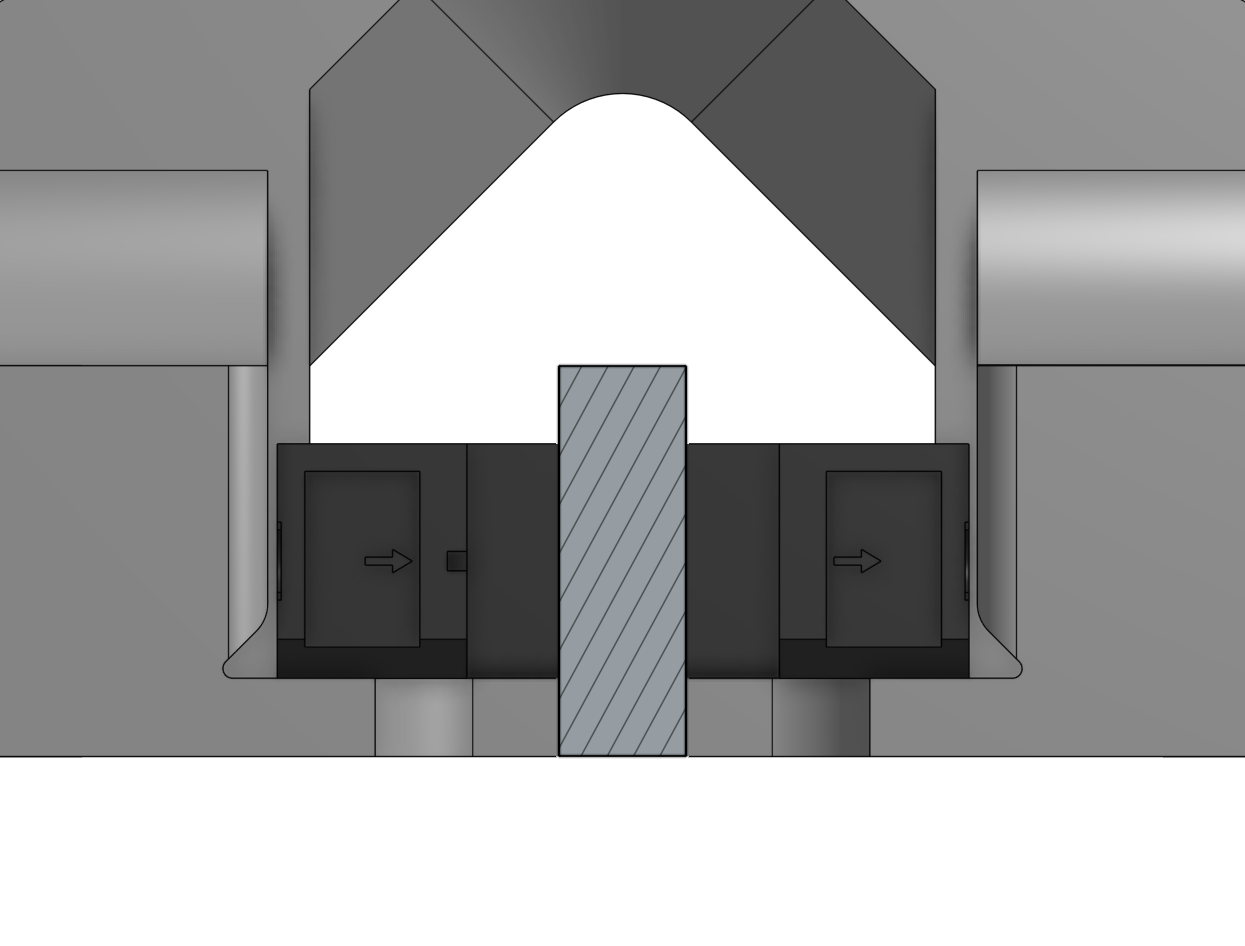

Top Plate

|

|

The bottom side of the top plate has the mates for the gasket and rotor bearings. As mentioned above, I would recommend only using the outer bearing race here. On the top surface are another jewel bearing cone and a v-groove race. Leave the cone empty, and only use the outer race with 3/8" balls.

Spool Plate

The Spool Plate could probably be printed combined with the Flexure Tube, but I separated them so that I could make the bearing races from a stiffer plastic like PLA. It has pockets for the other half of the coupler magnets, and a v-groove for the bearing on the bottom, and a recess for gluing on the Flexure Tube on top.

Flexure Tube (aka the actual paper towel holding part)

|

|

Guess it's pretty much been covered already above, but it's a flexi part, intended to be printed in TPU, but i've also made them from PETG (but much less 'flexi', of course).

- Details

- Parent Category: Just Playin and Concept Demo Projects

- Category: Flexure Fun

WIP

- Details

- Parent Category: Just Playin and Concept Demo Projects

- Category: Flexure Fun

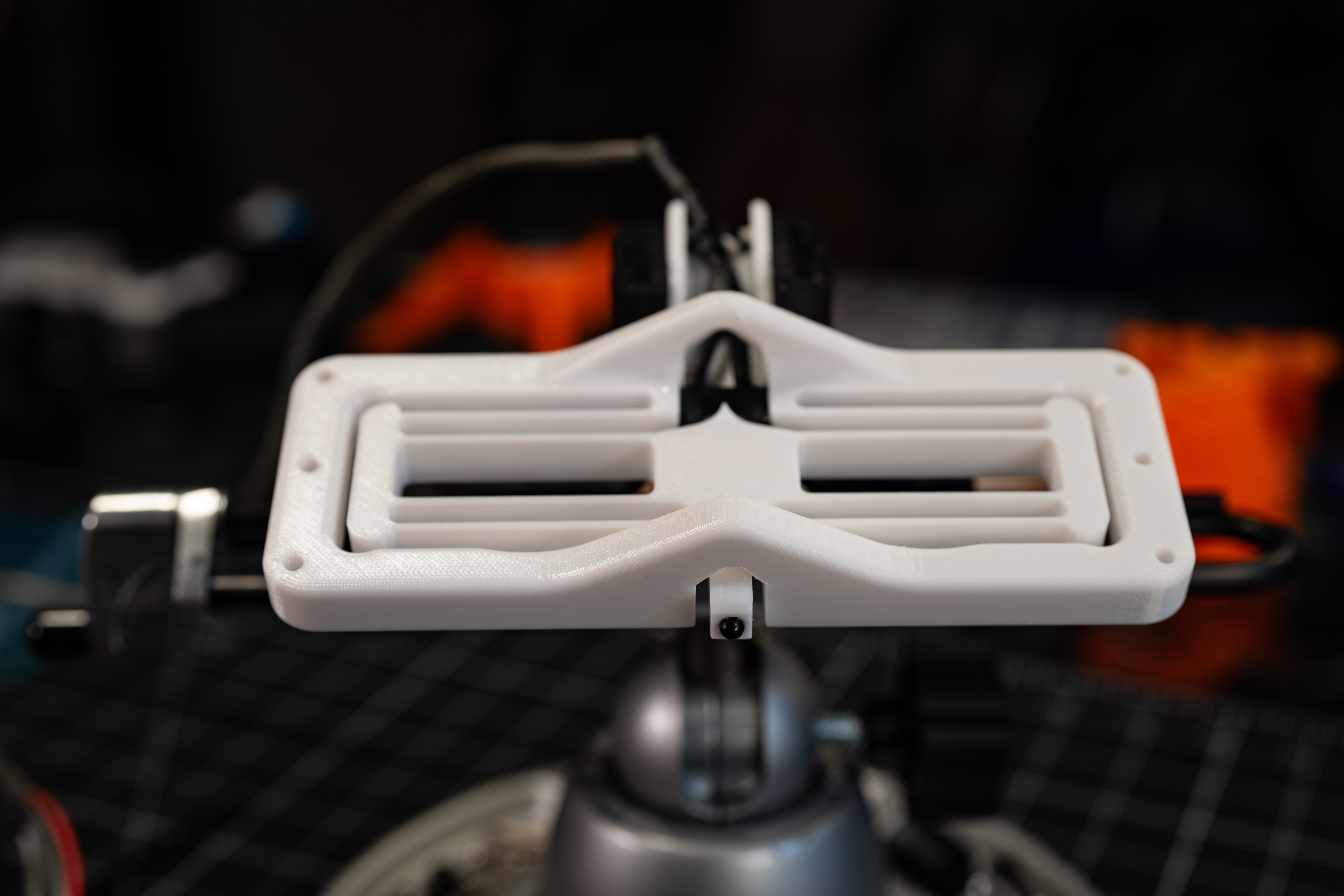

Build

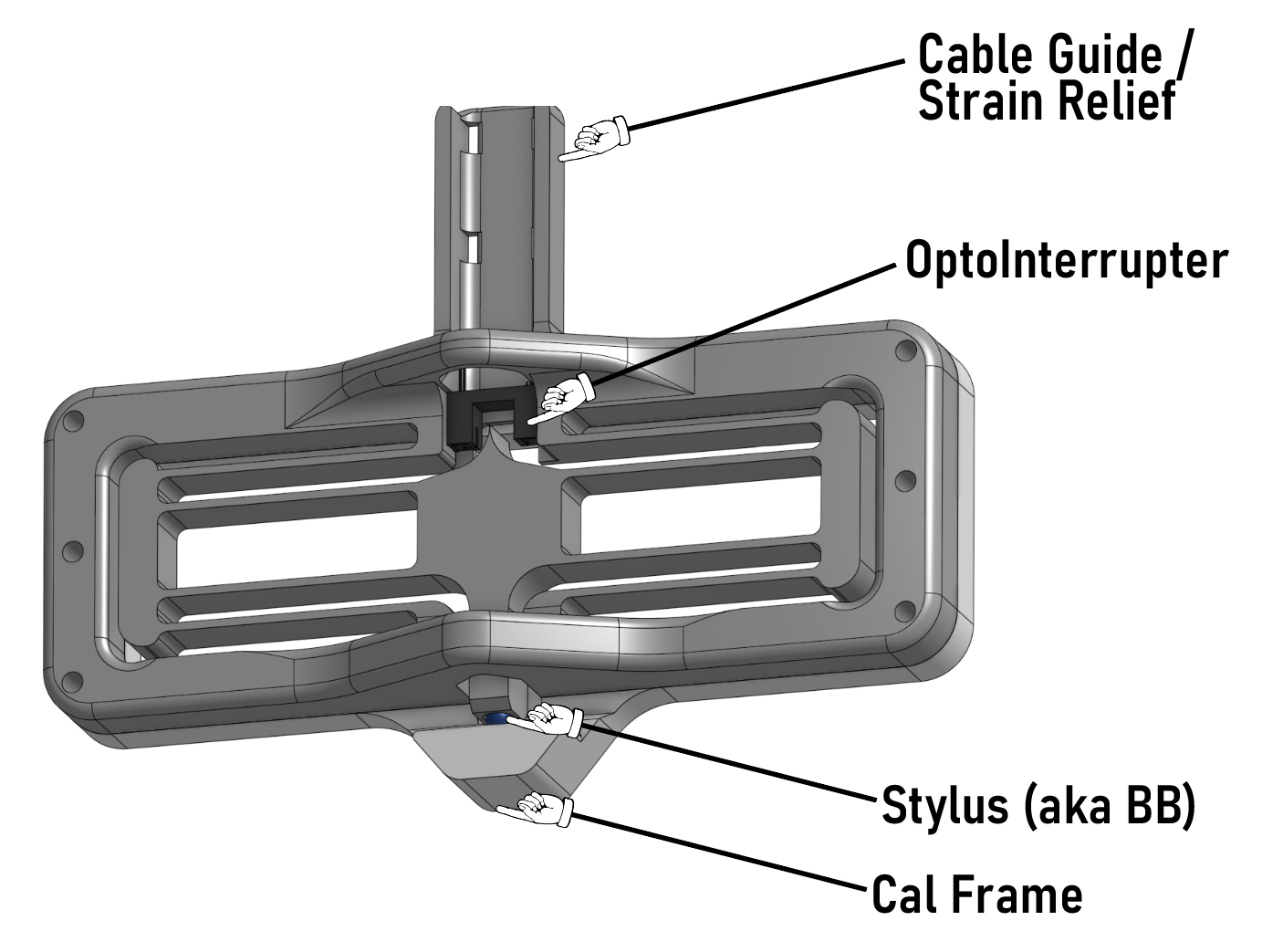

- Printed Parts:

- FlexureFrame_BuiltInBlade

- CalFrame - If you plan to calibrate similar to how I do below

- COTS

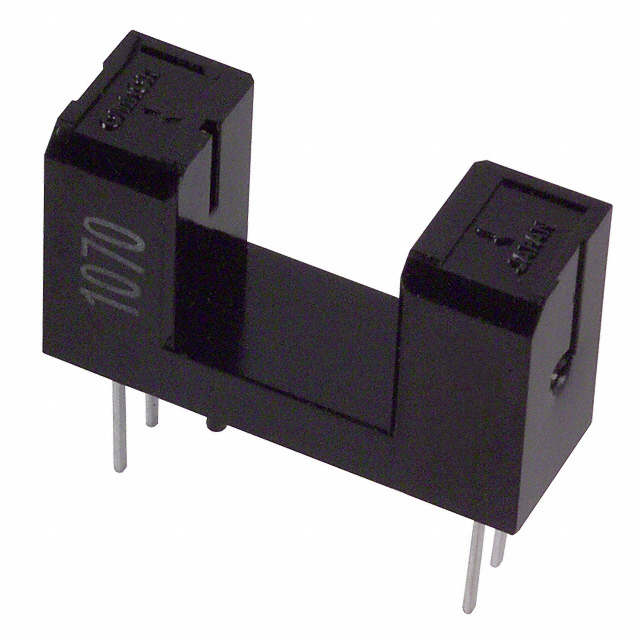

- EE-SX1070 - OptoInterrupter

- 4.5mm Steel Ball - aka a bb. This is your stylus tip. Anything hard, spherical, and around this diameter should work. I've been using these, partly for the hard anodized finish...no clue what the other part was :) but they've worked for me as styli and in bearings and such just peachy.

- Glue - I recommend super glue of your favorite variety. I used this medium viscosity stuff.

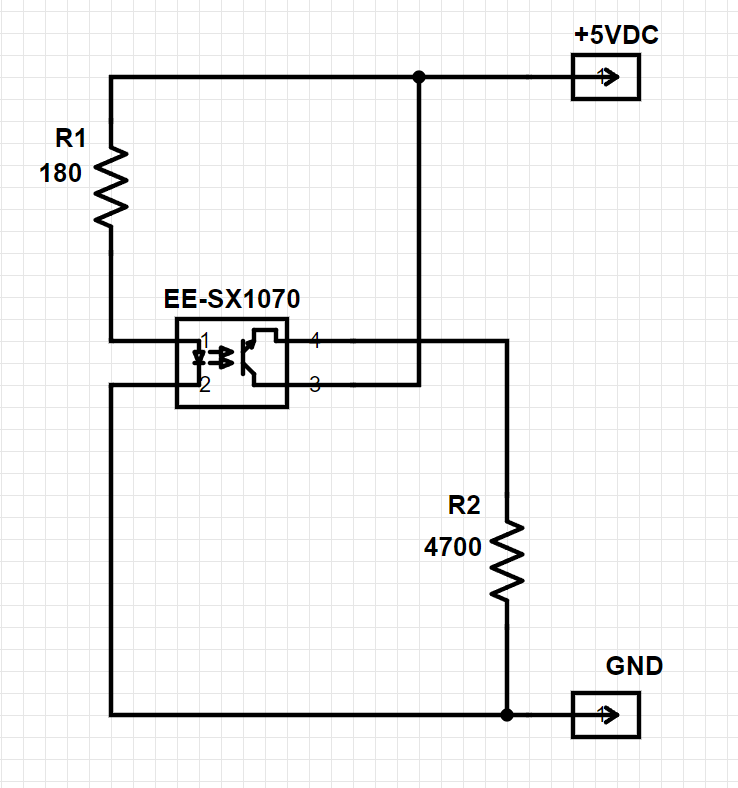

- Resistors - I used one 180 Ohm and one 4.7 kOhm

- Wire - I used some old scrap telephone wire

- Attach wire leads to the optointerrupter. I usually crimp on Molex female connector pins onto the ends of the wires. I then slide these on to the pins of the opto and then solder them secure. If you have a more elegant solution that you like, I'd love to hear about it in the comments, but this works well enough.

- Assemble the circuit (see Electrical section below for how I went about this one)

- Feed the wire leads through the arch above where the opto sits in the frame. Feed them all the way through so that the opto is approximately in the right spot. You'll set it's final spot shortly. Also, there are two sets of openings in the Cable Guide for zip ties to provide some strain relief. I like to go ahead and put the zip ties in at this step, but leave them as just loose loops. Waiting to tighten them once the glue has fully set after step 6.

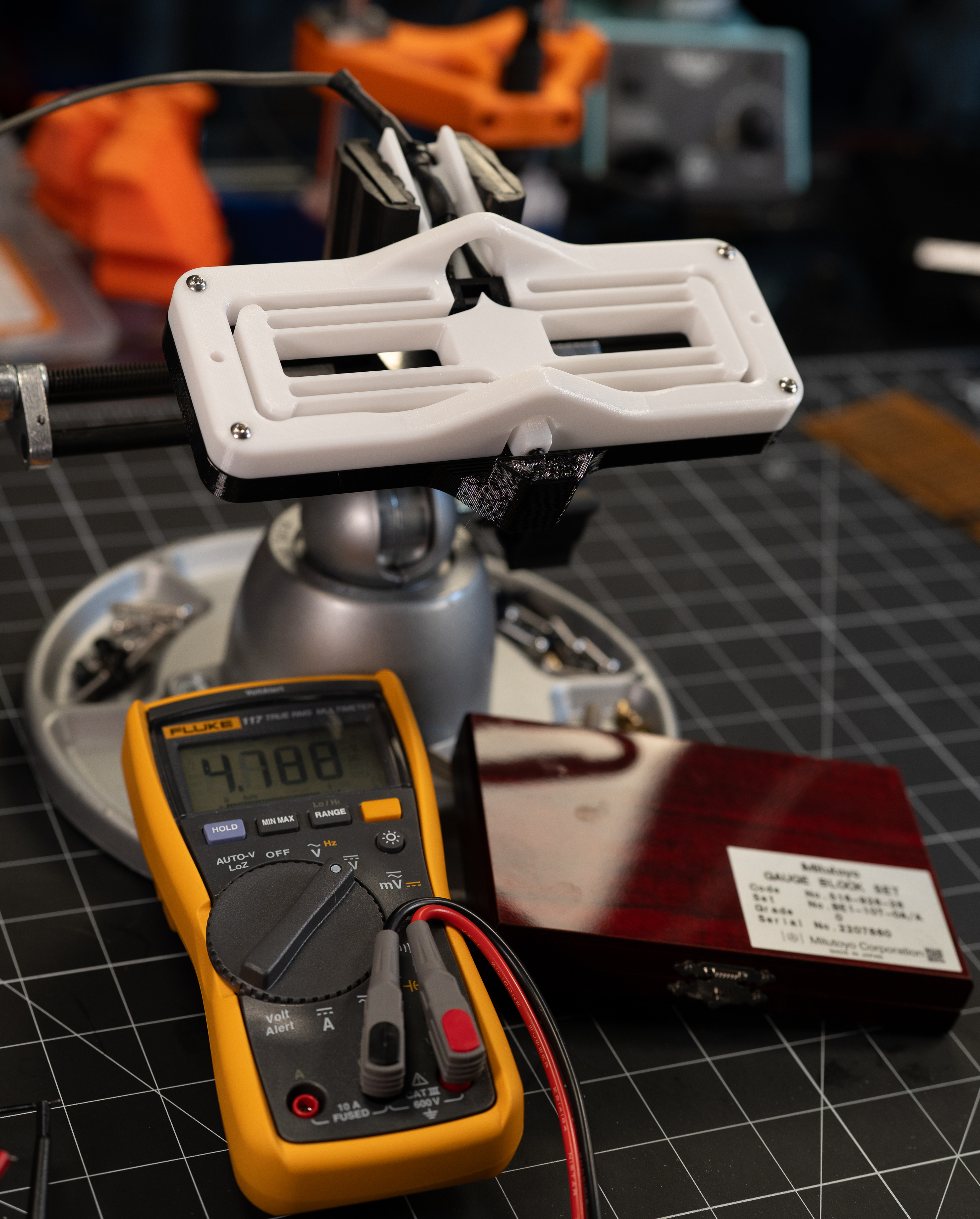

- Connect the wire leads to their appropriate connections on the circuit, and power on the circuit.

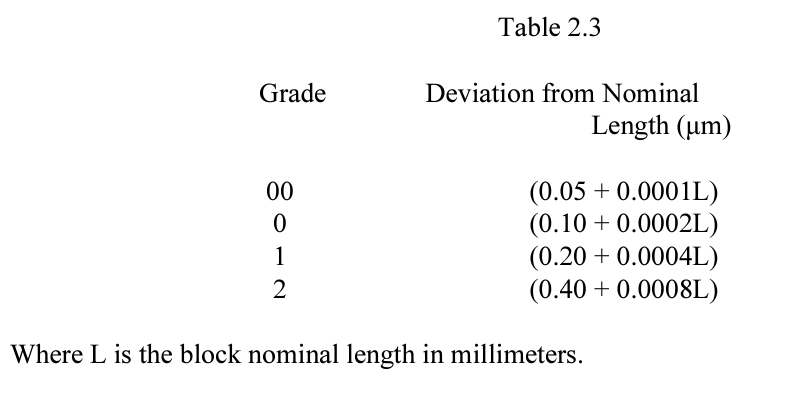

- Hold the opto so that the bottom side of it's U shape is pressed against the plane behind it, and slide it until the output voltage is ~5-10% below the voltage with nothing disrupting the beam. Make sure there is nothing causing the flexure to be deformed while setting this. The goal is to position it such that the plastic 'blade', is inside the measurement range at no displacement. The 5-10% is to try to get away from the highly nonlinear response expected at the ends of travel.

- Once the sensor is positioned to your liking, apply a small drop of glue between the side of the opto and the printed plastic wall next to it. I like to glue one side while using my hand to keep pressure on the other side. Once that side has set (30 seconds or so) I repeat it on the other side.

- Tighten the zip ties in the Cable Guide. Be careful to make sure you don't put a strain between the zip tie and opto. The goal of these zip ties is to isolate the sensor from any downstream tugs, bends, etc.

- Put a small drop of glue in the cone for the stylus, and apply some pressure to the stylus/ball while the glue sets. Don't push too hard, and preferably provide some support so you aren't just pressing against the flexure.

Electrical

Or, to tie this in with an Arduino, instead of just reading the voltage on a multimeter:

Here I've just added in an Arduino Nano (I used one of these generic versions) to read the sensor voltage.

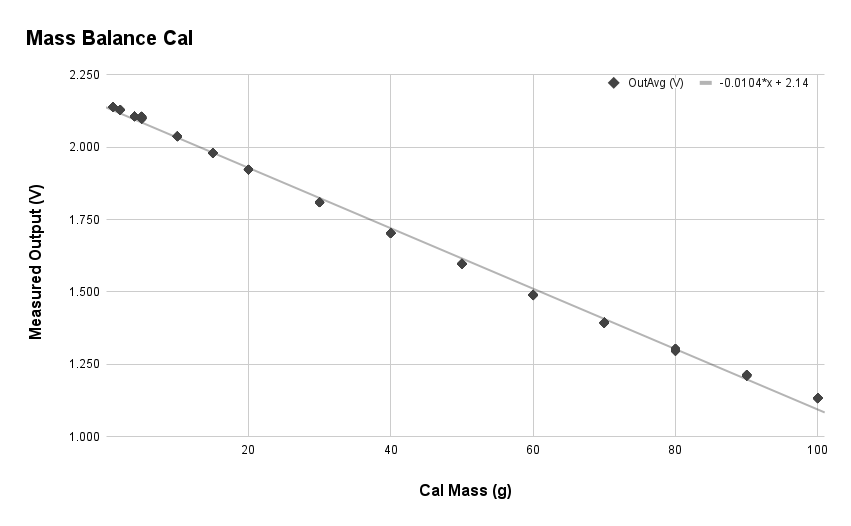

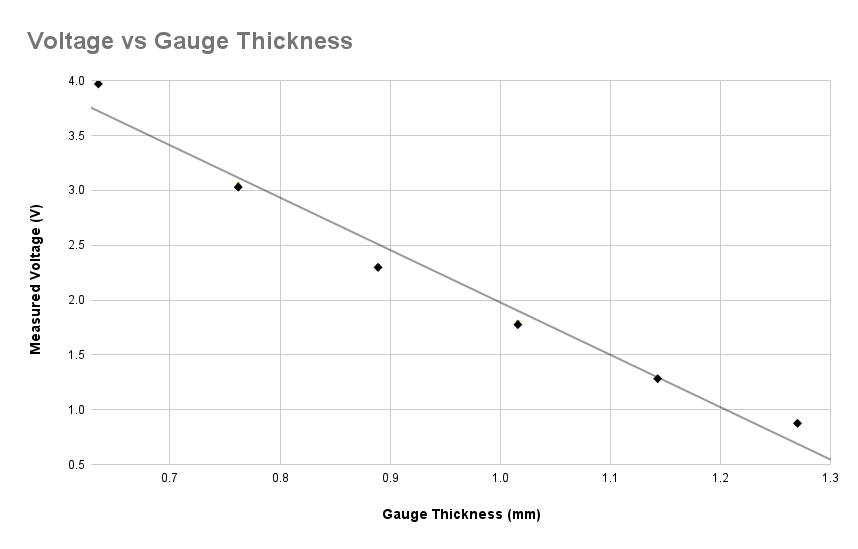

Calibration

Process

Results

Design Notes

2024/01/20 - Initial design

2024/01/22 - V2